Military History

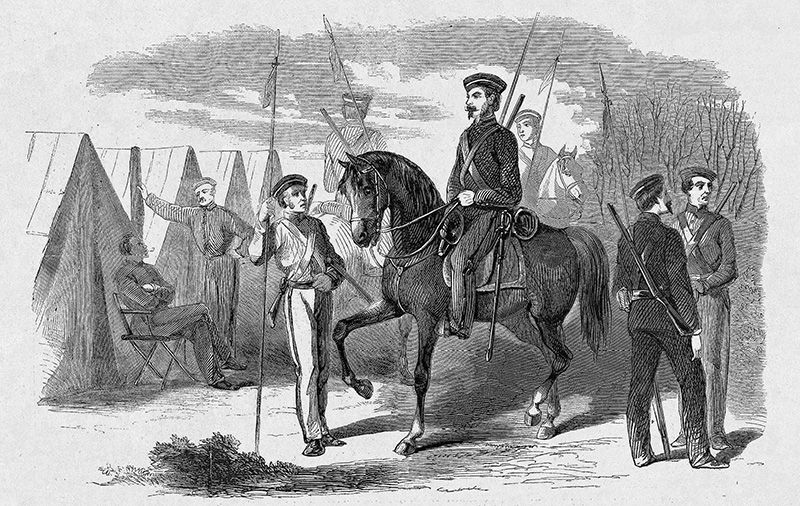

Harper’s Weekly, December 21, 1861.

Colonel Rankin’s lancer regiment, sketched at Detroit in 1861 by Mr. B.R. Erman.

When Johnny (Canuck) Comes Marching Home Again: Canadians in the American Civil War, 1861–1865

by Geoff Tyrell

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Major Geoff Tyrell is a logistics officer serving at 7 Canadian Forces Supply Depot. A graduate of the Royal Military College, he has deployed to Afghanistan and Ukraine.

Introduction

During the 19th Century, Canadians fought on numerous foreign battlefields, ranging from the Crimean Peninsula to the South African veldt. Less well-known is the story of Canadians serving south of the border during the American Civil War. Between 1861 and 1865, Americans fought a bloody conflict that was the culmination of decades of contention over both the state of the nation and its future. At its heart was the question of slavery, and whether African-Americans would live as free men or spend their lives in fear of forced bondage. The combination of westward expansion, the growing momentum of the Abolitionist movement, and increasingly-fractious debates over the limits of federal and state law finally exploded in the first shots fired by Confederate secessionists at Fort Sumter on 12 April 1861.

Over the next four years, more than three million Americans served in either the Union or Confederate armies. Of those who bore arms, more than 600,000—or twenty percent of the total number of enlistees—lost their lives to combat, wounds sustained in battle, or disease.1 It was a transformative event in the history of America, and it can be regarded as the first modern war of the Industrial Age. Many of the key hallmarks of the struggle—conscription, strategic use of railways, and armoured warships, to name but a few—would come to feature prominently in major conflicts throughout the rest of the 19th Century, and on into the First World War.

The nation of Canada was still in its infancy during this time, and Canadian2 attitudes with respect to the Civil War were complex. The British government abolished slavery across its empire in 1834, and popular Canadian sentiment opposed the continued practice of human bondage in the United States.3 Cross-border economic and cultural links between Canada and America were strong, and more than 250,000 Canadians were living in the United States as of 1860.4 While this suggests a prevailing affinity for the Union cause, support for the Confederacy was unabashed in many quarters of Canadian society. With Britain and her colonies officially neutral, but benefiting from commerce with the Confederacy, anti-British—and by extension, anti-Canadian—sentiment swelled throughout the Union states.5 Diplomatic incidents such as the Trent Affair, [discussed in depth later – Ed.] exacerbated tensions between the British and Union governments, and fears of an American invasion prompted the hasty reinforcement of Canada’s defences. The spectre of another American invasion was daunting for Canadians, as America’s Civil War threatened to spill beyond its national borders.

Despite Anglo-American animosity, tens of thousands of Canadians crossed the border to fight in the conflict. Exact numbers are impossible to determine,6 but conventional estimates suggest that somewhere between 35,000 and 50,000 Canadians bore arms in the American Civil War, the vast majority donning Union blue.7 Canadian reasons for participating in the struggle varied from belief in the cause, a desire for adventure or money, or victimization at the hands of ruthless recruiters. It is impossible to examine in detail the experiences of all those Canadians who served. Instead, this article will examine three examples of the many ways in which Canadians, by one road or another, became caught up in the conflict.

McCord Museum/I-17901.1

Arthur Rankin in Montréal, 1865.

An Ambitious Failure: Arthur Rankin’s Lancers

Arthur Rankin, the son of an Irish schoolteacher and the American-born daughter of a British Army officer, presents a fascinating character study. Born in Montreal in 1816, Rankin ran away from home as a young teenager to work as a cabin boy on a trans-Atlantic packet boat.8 He returned to Canada four years later, failed as a farmer and land surveyor, fought a duel with a Detroit lawyer over a woman’s affections, and obtained an ensign’s commission in the local militia. In September 1837, he achieved some notoriety when he freed a recaptured slave at gunpoint aboard a Cleveland-bound steamship.9 Rankin saw active service during the Patriot War of 1838, and fought against the insurgents of the Hunters’ Lodges during the Battle of Windsor. Discharged from the militia five years later, he toured the British Isles with a group of Ojibway, worked as a mining surveyor and railroad investor,10 and entered local politics. Rankin was a well-known figure in Canada West by the time of the Civil War’s outbreak.

In July 1861, Arthur Rankin was elected as Member of Provincial Parliament for Essex County. However, his interests lay beyond the mere representation of his constituents. That same month, he met with prominent Detroit Unionists and state government officials to explore ways in which he—and by extension, Canada—could come to the aid of the Union cause. Rankin planned to raise a regiment of cavalry for service in the Union Army, to be known as the First Michigan Regiment of Lancers.11 Envisioned as a 1,600-man unit, the Lancers were to be led by Canadian officers with British Army experience and the ranks were to be filled by eager Canadian volunteers. Rankin’s Michigan compatriots were so impressed by his proposal that he was taken to Washington in late-August to present his idea to no less a pair of prominent figures than President Lincoln and Secretary of State Seward. Lincoln was apparently charmed by Rankin’s enthusiasm, and on 11 September 1861, a warrant was issued for the creation of the regiment.12 Among varied (but limited) efforts by Canadians to create volunteer units for service during the Civil War, the Lancers were the most successful.

The Lancers were not Rankin’s first brush with military adventurism. In 1854, at the outbreak of the Crimean War, he wrote to senior British officials offering to raise a battalion of Canadian volunteers for service in the campaign. In the end, he was not taken up on his offer. Throughout his life, Arthur Rankin developed a reputation for being a showman, revelling in public attention and notoriety. It should therefore come as no surprise that word of his Lancers was almost immediately leaked to the press, prompting mixed reactions on both sides of the border. For instance, the Toronto Globe enthused about the romantic image of the Canadian volunteer cavalryman, who “…with…revolver in his left hand, his sabre in his right, guiding his lance mainly with his leg, and a horse under good training can deal out death upon the front and each flank at the same time.”13 The Montreal Gazette was somewhat more circumspect: “There are not many men in Canada better known, for his somewhat Quixotic eccentricities than Arthur Rankin.”14

Library and Archives Canada, e000755406

Recruiting poster, Rankin Lancers (c.1861).

The regiment’s organizers embarked upon an ambitious recruiting program, distributing handbills calling for volunteers, and making arrangements to stand up the unit in Detroit. Meanwhile, Rankin became the subject of furious debate in the leading Canadian newspapers of the day. The pro-Confederate Toronto Leader denounced him for violating the Foreign Enlistment Act, prompting Rankin to defend himself in print. On 5 October 1861, he wrote a rebuttal letter to the Leader denouncing it as “a tool of Jefferson Davis,”15 and claimed that the Act applied only to the British government and not to private British subjects. Despite censure in the press, Rankin was determined to press ahead with his regiment of volunteers.

Unfortunately for Rankin, Canadian authorities did not concur with his interpretation of the Foreign Enlistment Act. The day after his letter was published, he was arrested in Toronto for violating the legal ban on British subjects serving in foreign conflicts. Naturally, Rankin pleaded not guilty, and over the course of a three-day trial, the charges against him fizzled out for a want of evidence (despite the fact that his name was clearly listed on recruiting posters for the unit) and questions of jurisdiction. Although never convicted, Rankin suffered repercussions for his pro-Union enthusiasm: he was dismissed from his position as commander of the Ninth Military District and deprived of his militia commission. Following the Trent Affair, he resigned his American commission, writing to the Detroit Free Press that the possibility of a war between Great Britain and the United States forced him to return to his first loyalty as a British subject.16

But what of his Lancers? Despite official condemnation by Canadian officials, the regiment mustered more than six hundred men by December 1861. Bereft of its leader, the unit began to lose cohesion, and escalating hostilities between the United States and Britain deterred more Canadians from volunteering for service with the regiment. Between January and March 1862, it quietly disbanded and its soldiers either transferred to other Union cavalry regiments, or were discharged from service.

In the end, Arthur Rankin’s Lancers never fought in defence of the Union, and created an embarrassing episode for both Canadian and British governments.17 Questions still linger over Rankin’s motivation as, despite the Cleveland incident, he was never vocally abolitionist in his opinions. Most likely, the desire for fame and military glory influenced his enthusiasm, and ultimately condemned his Lancers to defeat without ever setting foot on the battlefield.

A Family Enterprise: The Wolverton Brothers Go to War

As Arthur Rankin concocted his plan to raise a volunteer cavalry unit for the Union Army in the summer of 1861, thousands of his countrymen were already south of the border and wearing federal blue. In the decade preceding the war, more than 100,000 Canadians had immigrated to the United States, largely in search of economic opportunity.18 This cadre furnished a number of volunteers for service during the conflict, among which were four brothers from the small village of Wolverton in Oxford County, Canada West: Alfred, Alonzo, Jasper, and Newton Wolverton.

The four Wolverton brothers were the sons of an American immigrant who had left New York State in the 1820s and settled south of present-day Kitchener.19 To support their father’s cross-border lumber business and further their education, the brothers moved to Cleveland in 1858. On 21 July 1861—the day on which Union and Confederate forces clashed in the war’s first major battle at Bull Run—Alfred, Jasper, and Newton enlisted as teamsters in the Union Army.20 They ultimately found themselves serving in Washington with the Quartermaster’s Department, transporting ammunition to the newly-created Army of the Potomac as it sought to defend the approaches to the federal capital against the alarmingly-successful Confederate Army.

Jasper was the first of the Wolverton boys to perish during the war, succumbing to typhoid fever in Washington on 12 October 1861.21 Less than one month after his death, a Union warship seized a British mail steamer—the RMS Trent—that was carrying two Confederate diplomats to London, where they hoped to receive official recognition of the Confederacy from Lord Palmerston’s government. The ensuing diplomatic confrontation between British and Union governments stoked fears that an American invasion of Canada was imminent, necessitating hasty preparations for war north of the border. More than 11,000 British regulars arrived in eastern Canadian ports and were dispersed inland, joining nearly 50,000 Canadian militia in varying states of preparedness.22

The prospect of war between their motherland and the nation in whose army they served was unsettling for the thousands of Canadians in the Union Army. Some began to doubt their commitment to the Union cause when faced with the prospect of being ordered north to invade their own country, and they contemplated desertion. Amidst these tensions, a group of Canadian volunteers came together in Washington to present their concerns to the Union leadership. Surprisingly, the fifteen-year-old Newton Wolverton was elected as their spokesman. Leveraging his contacts in the Quartermaster’s Department, the young Canadian from Oxford County secured a brief meeting with none other than Abraham Lincoln himself.23 The President assured Wolverton that he had no intention of pursuing a war with either Britain or Canada, and cooler heads gradually prevailed in resolving the Trent Affair.24

The Wolverton family suffered its second loss on 24 April 1863, when Alfred died of smallpox while serving in Washington.25 By the end of that year, young Newton Wolverton was discharged from the Union Army and returned home to Oxford County. With his departure, Alonzo remained the only one of the four Wolvertons still bearing arms for the Union. Like his brothers, Alonzo began the war as a teamster, enlisting with the 20th Independent Battery of the Ohio Light Artillery in 1864. In the spring of that year, Alonzo and his comrades were garrisoned in Chattanooga, Tennessee, and then joined the Union advance as General William Tecumseh Sherman launched his Atlanta Campaign, intent upon seizing the eponymous city and devastating the heartland of the Confederacy.

Library of Congress/LC-USZC4-1732

Battle of Franklin, 30 November 1864.

Alonzo and the 20th Independent Battery found themselves on the flank of Sherman’s march, repelling attacks by Nathan Bedford Forrest’s Confederate cavalry as the Union Army manoeuvred towards Atlanta. After Sherman captured the city in early September, Confederate General John Bell Hood counter-attacked through northern Georgia, resulting in Alonzo Wolverton and several of his comrades being taken prisoner. His captivity was short-lived, as he was paroled by his jailers and quickly re-joined Sherman’s forces.26 Alonzo saw action again at the Battle of Franklin, on 30 November, and the Battle of Nashville, 15–16 December, when Hood’s Army of Tennessee was decisively destroyed. In a letter to his sister Roseltha, Wolverton described the fighting at Franklin as particularly brutal:

“[T]he rebs seemed determined to conquer or die. [T]hey made thirteen desperate charges, several times they planted their colors within feet of our cannon and our men would knock them down with their muskets or the artillerymen with their sponge staffs or handspikes.”27

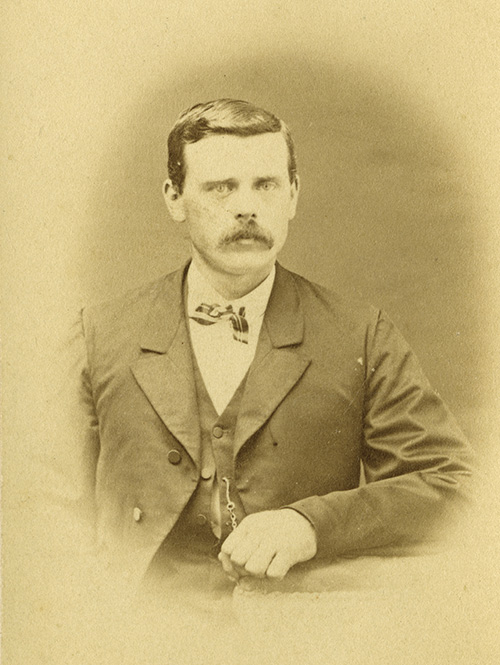

Archives of Ontario/F 4354-4-0-12

Alonzo Wolverton.

The day following Hood’s defeat at Nashville, Corporal Alonzo Wolverton accepted a commission as a Second Lieutenant in D Battery of the 9th Regiment, U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery.28 The rest of his war passed by in comparative quiet, with his regiment remaining in garrison at Nashville. Robert E. Lee surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House on 9 April 1865, and the remaining Confederate commanders followed suit over that spring. Alonzo Wolverton was discharged on 2 August 1865, and made his way home to his family’s village in Oxford County.

Of the four Wolverton brothers, two—Alfred and Jasper— died of disease during their service and were buried in the United States.29 Newton, the youngest, took his discharge and left America in 1863. He was soon back in uniform, this time in the dark green of the 22nd Oxford Rifles, a Canadian militia unit. Newton spent the next several years on periodic duty with his regiment, guarding the Canadian border against a new threat from the south: the Fenian Brotherhood.30

The story of the Wolverton brothers is perhaps typical of Canadians who found themselves serving in the Union Army during the Civil War. When the conflict began, they were already living in the United States. Both the desire for adventure and the financial incentive of recruiting bonuses led them to serve a country that was not their own. For Alonzo and Newton, the war left a lasting impression upon their lives, and it was the defining event of their youth. In this they were not alone, as thousands more of their countrymen crossed the border to take up the Union’s call to arms.

Queen’s University Archives, Francis Moses Wafer fonds, Locator 3178.1-1-7

Francis Moses Wafer.

The Bloodiest of Classrooms: Frances Wafer Interns with the Army of the Potomac

Francis Moses Wafer was born near Kingston, Ontario on 31 July 1830, the son of a Roman Catholic farming family of Loyalist stock. The Civil War’s outbreak found him a student in Kingston, studying at both Queen’s University31 and the Kingston General Hospital. While his education made him much better prepared for his wartime role than many of his peers in blue,32 medicine was still an ill-paying profession by the standards of the 19th Century. Nonetheless, Wafer was intrigued by the prospect of furthering his practical medical skills by way of service with the Union Army, following the conclusion of the 1862–1863 school year at Queen’s. At the end of the academic term, he made his way to the United States and was duly appointed as the assistant surgeon of the 108th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment.

The outbreak of the Civil War caught the Union Army woefully ‘flat-footed’ in many respects, from men to materiel. Prior to the conflict’s outbreak, the American military was first and foremost a frontier force, safeguarding the nation’s borders and contributing to the country’s gradual expansion westward. Neither the Union nor the Confederacy were prepared for an industrialized clash of arms that would last for years, and systemic failures in both military medical organization and preparation had lethal consequences for those fighting on the battlefield.

The Union Army began the Civil War with a mere 114 doctors in service, of whom twenty-four resigned to join the Confederacy.33 Even then, these medical professionals had spent much of their careers in isolated frontier garrisons, without access to the most current training, and with limited exposure to any larger community of medical practitioners. Following mobilization in the spring of 1863, the Union Army required each regiment to provide its own surgeon, a policy that guaranteed a frightening variation in the standard of care provided to wounded and ill soldiers.34

The 108th was raised for Union service in the summer of 1862, and was bloodied at both Antietam (September 1862) and Fredericksburg (December 1862). Within the first three months of its service, the regiment sustained nearly 300 casualties.35 By the time Wafer joined the unit in late-March 1863, it was already a veteran regiment of the Army of the Potomac. Along with tens of thousands of their fellow Union troops, Wafer and the 108th languished in camp through the spring of 1861, beset by typhoid fever and dysentery. During that time, the Army’s commander, General Joseph Hooker, prepared for a campaign that would destroy Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and open a path to the Confederate capital at Richmond.

Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-12811/Edwin Forbes

Union field hospital (Second Corps) near Chancellorsville battlefield.

Wafer’s own baptism by fire came at the Battle of Chancellorsville in early-May 1863. The 108th came into contact with Confederate forces on 2 May, and Wafer’s proximity to the front line gave him the grim realization that “…for the first time I felt that in a few moments I would be literally ‘Staring Death in the Face.’”36 With his fellow surgeons in the 2nd Brigade,37 Wafer withdrew to a hastily-established brigade medical station in the rear and began to treat casualties as they were evacuated from the front. Coming under artillery and rifle fire was a new and unnerving experience for the untried Wafer. Nonetheless, he persevered in treating his regiment’s casualties. The 108th went into battle numbering less than 400 soldiers, a dramatic decrease from the 950 who had enlisted less than one year before.38

Chancellorsville was a defeat for the Army of the Potomac. Hooker failed to achieve his operational aims, and Lee’s counter-attack into Pennsylvania sent Union forces scrambling to both contain the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, and to defend Washington. As the Gettysburg Campaign began on 3 June 1863, Lee’s forces began their advance north from Fredericksburg. The Confederates were shadowed by the Army of the Potomac, albeit belatedly. Hooker was initially unaware of Lee’s intent, and the two armies came together in a meeting engagement at Gettysburg on the first of July.

Wafer spent the month following the federal disaster at Chancellorsville serving in a divisional field hospital near Potomac Creek. He re-joined the 108th New York on 7 June, and one week later, the regiment was ordered to march in pursuit of the Confederates. On the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg, the 108th was ordered to defend a battery of Union artillery in the centre left of the federal line. At around 7:00 AM that day, “a thin straggling line of men in brown slowly advanced through a wheat field about three-quarters of a mile to our front. These were the enemy’s skirmishers.”39 Coming under heavy rifle and artillery fire, the 108th New York sustained an increasing number of casualties throughout the day until the Confederate attack ceased late that night.

Science History Images/Alamy Stock Photo/HRP4FP

Battle of Gettysburg, Pickett’s Charge, 1863.

As dawn broke on 3 July, Lee, determined to renew his assault, ordered General James Longstreet to take three Confederate divisions and attack the Union II Corps in force. Wafer witnessed what became known as the “high-water mark of the Confederacy:” Pickett’s Charge. More than 12,000 Confederate soldiers, “emerging from the woods immediately in front of the 2nd Corps…in solemn grandeur several lines deep…across the open plain more than half a mile of which was fully exposed to the fire of our artillery”40 came under withering bombardment from Union troops. Although some Confederate soldiers advanced to within mere yards of the federal line, their advance was defeated, with more than half the rebels falling dead, wounded, or were captured. Pickett’s Charge failed and, exhausted, Lee’s forces began their withdrawal late the next day as news arrived of Grant’s victory at Vicksburg.

Their role in halting the Confederates at the battle’s critical moment cost the 108th New York dearly: more than one-third of the roughly 250 men of the regiment who had joined the battle became casualties.41 As Wafer and his comrades began to grasp the impact of Lee’s defeat, the Union Army gained a renewed sense of confidence that their opponents were far from invincible. Lee never again launched a strategic offensive into the north, and spent much of the remainder of the conflict on the defensive against the Union Army as it penetrated deeper into the Confederacy.

Francis Wafer’s service to the Union did not end at Gettysburg.42 Remaining with the 108th, he campaigned through Virginia at such Battles as the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House, and Cold Harbor. He was likely present at Appomattox Court House on 9 April 1865, when Lee finally surrendered his much-diminished army to Grant, precipitating the final collapse and defeat of the Confederacy.

Lebrecht Music & Arts/Alamy Stock Photo/ERG8K3

Surrender at Appomattox Court House, 9 April 1865. Confederate Army of Northern Virginia commander Robert E. Lee (left) officially surrenders to Union commander Ulysses S. Grant, accompanied by Generals Merrit and Parker.

The 108th New York was mustered out of service six weeks after Lee’s surrender. Francis Wafer returned to Kingston in July and resumed his medical studies at Queen’s. He graduated in March 1867 and entered private practice that same year. Although he survived his service in the Union Army, the war left its mark on Doctor Wafer. He was plagued by chronic ill-health beginning in 1865, and eventually died from illness on 9 April 1876. His surviving relatives spent years in the fruitless pursuit of a pension from the American government. Francis’ contribution to the Union cause, like that of many of his fellow Canadians, passed largely unnoticed by the United States.

The End of the War and the Beginning of Canada

Canadian experiences during the American Civil War varied widely. Arthur Rankin never heard a shot fired in anger, although many of his volunteers did as they went on to serve in other regiments. The Wolverton brothers lost half their number to the conflict’s greatest killer: disease. And finally, Francis Wafer was afforded a rare opportunity to apply his medical education in armed conflict, that most dire of circumstances. While it could be argued that Canadians did not make a grand impression on the Civil War, the Civil War certainly left its mark on Canadians.

Library and Archives Canada/Acc. No. 1946-35-1

Battle of Ridgeway. Desperate charge of the American Fenians under Colonel O’Neill near Ridgeway Station, 2 June 1866.

Hostility between the Union government and Great Britain laid bare just how vulnerable British North America remained to American military aggression and expansion. The exorbitant cost of defending Canadian territor—and Canadians’ own half-hearted interest in their defence—forced the British government to re-examine how far it was willing to invest in a remote colony on the far side of the Atlantic. Canadians themselves—caught in the middle, of varied opinion regarding America’s masochistic struggle, and increasingly independent-minded—came to believe that taking their nation’s destiny into their own hands was the best choice for its people.

The Dominion of Canada was born on 1 July 1867. Across the new nation, many of those celebrating would doubtless have been Canadian veterans of both the Union and Confederate armies, their lives forever shaped by their service in that conflict. While the role of Canadians in the American Civil War remains (and is likely to remain) a seldom-explored realm of Canada’s history, it is no less worthy of recognition than the service of Canadians on other foreign battlefields throughout the 19th Century.

Notes

- The American Battlefield Trust, at https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/civil-war-facts. Accessed 13 August 2018.

- As Canada did not exist as a nation during this time, the term British North American is more common in scholarship on the subject. However, the terms Canada and Canadian will be used for simplicity’s sake.

- John Graves Simcoe, the Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada from 1791-1796, was supportive of the Abolitionist cause and presided over the passage of the province’s Act Against Slavery. Passed on 9 July 1793, the Act forbid the introduction of new slaves into Upper Canada and granted freedom to children born to female slaves once they reached the age of twenty-five.

- Danny R. Jenkins, British North Americans Who Fought in the American Civil War, 1861-1865 (Ottawa: MA thesis, University of Ottawa, 1993), p. 10.

- William Seward, Lincoln’s Secretary of State, warned the British minister to the U.S.A. that British recognition of the Confederacy would lead to war, beginning with an invasion of Canada. John Boyko, Blood and Daring: How Canada Fought the American Civil War and Forged a Nation (Toronto: Alfred A. Knopf Canada, 2013), p. 64.

- Several factors preclude precision when it comes to determining how many Canadians fought in the war: record keeping was often faulty, recruits’ hometowns were not always identified, and British invocation of the Foreign Enlistment Act of 1819 made it illegal for British subjects to participate in the conflict.

- Jenkins, p. 23.

- John E. Buja, Arthur Rankin: A Political Biography (Windsor: MA thesis, University of Windsor, 1982), p. 1.

- Ibid, p. 3.

- Rankin was implicated in the so-called “Southern Railway Scandal” of 1857.

- Boyko, p. 115.

- Buja, p. 97.

- Boyko, p. 116.

- Buja, p. 98.

- Ibid, p. 99.

- Robin W. Winks, The Civil War Years: Canada and the United States (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1998), p. 190.

- Seward officially denied any involvement in the scheme, although he allowed that American authorities could not prevent immigrants from serving in the Union forces.

- Boyko, p. 112.

- David A. MacDonald and Nancy N. McAdams, The Wolverton Family 1693-1850 and Beyond, Volume II (Albuquerque, NM: Penobscot Press, 2001), p. 882.

- A.N. Wolverton, Dr. Newton Wolverton: An Intimate Anecdotal Biography of One of the Most Colourful Characters in Canadian History (Vancouver: Unknown Publisher, 1933), p. 24.

- MacDonald and McAdams, p. 885.

- Boyko, pp. 97-101.

- Ibid, p. 120.

- Ever-pragmatic, Lincoln concluded that a concurrent war with both the Confederacy and Britain would be a disaster for the Union. Eventually, the two seized Confederate diplomats were released from custody and the actions of the Union warship’s captain were disavowed.

- MacDonald and McAdams, p. 885.

- Boyko, p. 135.

- Alonzo Wolverton, letter to his sister Roseltha Wolverton Goble, dated 4 December 1864. Archives of Ontario, at: http://www.archives.gov.on.ca/en/explore/online/fenians/big/big_16_dec4b.aspx.

- Adjutant-General’s Office, Official Army Register of the Volunteer Force of the United States Army for the Years 1861, ’62, ’63, ’64, ’65, Part VIII (Washington, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1867), p. 156.

- Common at the time, disease remained the great killer of both armies during the Civil War.

- Composed largely of Irish immigrant veterans of the Union Army, the Fenians launched several raids into Canada between 1866 and 1871, in the belief that seizing Canadian territory would force the British government to withdraw from Ireland.

- Then known as Queen’s College.

- Some fifty Union surgeons were court-martialled for incompetence during the Civil War.

- Francis M. Wafer, A Surgeon in the Army of the Potomac, Cheryl A. Wells, (ed.), (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2008), p. xxvii.

- Ibid, p. xxviii.

- Steve A. Hawks, The Civil War in the East, entry for the 108th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment, at: http://civilwarintheeast.com/us-regiments-batteries/new-york-infantry/108th-new-york/. Accessed 26 November 2018.

- Wafer, p. 21.

- Of the 3rd Division, II Corps.

- Wafer, p. 24.

- Ibid, p. 41.

- Ibid, p. 47.

- Ibid, p. 49.

- Francis Wafer was not the only Canadian doctor serving at the battle. Solomon Secord, a descendant of the famed Laura Secord, was a surgeon in the 20th Regiment, Georgia Infantry. He was captured after he elected to remain with the wounded while Lee’s remaining forces withdrew (Boyko, p. 134).