Military History and Tactics

CPA Media Pte Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo/2B00W8F

US forces supported by a UH-1D Huey helicopter in action somewhere in South Vietnam, circa 1966.

Counterinsurgency and Hybrid Warfare in Vietnam

by Ismaël Fournier

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

Ismaël Fournier is a former infantryman with the 3rd Battalion of the Royal 22nd Regiment, who deployed with them to Bosnia in 2001, and then to Kabul and Kandahar in Afghanistan in 2004 and 2007 respectively. Severely wounded in an IED explosion during the latter deployment, and after multiple restorative surgeries, Ismaël made a professional change to the military intelligence branch. Since then, he completed a baccalaureate, a master’s degree, and a Ph.D. in History from Laval University. Leaving the armed forces in 2019, he is currently employed by the Department of National Defence as an analyst specializing in strategy and tactics related to insurgencies and counterinsurgencies.

Introduction and Background

Since South Vietnam’s collapse in 1975, most studies dedicated to the Vietnam War have painted a highly negative portrait of the US military’s performance in Southeast Asia. Authors have frequently blamed the US Army for its tendency to favour conventional military tactics in a country deemed to be plagued by an insurgency. These same individuals have also widely criticized Military Assistance Command Vietnam’s (MACV) counterinsurgency strategy against the Communist guerrillas. Several went even further by asserting that no form of counterinsurgency would have been applicable in Vietnam. These theories have been advanced by many writers, including Lewis Sorley, Drew Krepinevich, Douglas Porch and many others. However, these views were also challenged by others, like Mark Moyar, Max Boot and Gregory Daddis. This article goes against the classic views regarding the US military’s “poor performance” in Vietnam, and suggests that US counterinsurgency initiatives were highly effective in the area, and went so far as to cause an unequivocal defeat of the Communist insurgency.

It will be further suggested that the execution of conventional military operations was in fact essential if US and South Vietnamese forces hoped to preserve the Republic of Vietnam (RVN). The overall analysis ultimately aims to demonstrate that the war was won by North Vietnam’s regular army, and not by the Communist insurgency. During the war, Communist leaders in Hanoi exploited both insurgent and conventional warfare tactics with their regular soldiers of the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and their guerrilla troops of the National Liberation Front, also known as the Vietcong. Such a modus operandi made Vietnam a hybrid warfare theatre. Too frequently, authors have neglected to explain the tactical reverberations that stemmed from Hanoi’s hybrid strategy. The NVA, unlike the Vietcong, did not use asymmetric guerrilla tactics, preferring to exploit conventional military doctrine. While the Vietcong was a guerilla force, some of its regiments also exploited conventional warfare tactics against the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) and US forces. Such is the nature of hybrid warfare; military forces will be targeted via asymmetric and regular tactics simultaneously, which highly complicates the tactical situation on the battlefield. Confronted with both regular and asymmetric threats, MACV had no alternative but to carry out both conventional and counterinsurgency military operations, a task most modern armies would find extremely difficult, even today. Although it required several years of adjustments coupled with multiple setbacks, US and ARVN forces managed to neutralize the insurgency in 1972.

Following the Tet Offensive in 1968, the US-led Civil Operations and Revolutionary Development Support (CORDS) counterinsurgency program, as well as the Phoenix program, ultimately brought about the downfall of the Vietcong. CORDS operations were largely inspired by the US Marine Corps’ (USMC) Combined Action Platoons (CAPs) concept. When the NVA took charge of military operations, its armies initiated major military offensives using classic mobile warfare supported by tanks and artillery, which led to their spring campaign in 1972, as well as the invasion that led to the fall of the RVN in 1975. MACV’s alleged “flawed counterinsurgency” and “reliance” upon conventional warfare had absolutely nothing to do with the military outcome of the conflict. In order to better understand these dynamics, we will conduct an analysis of the USMC’s counterinsurgency campaign, the effects of the CORDS and Phoenix programs on the insurgency, and the emergence of Vietnam as a conventional war theatre in 1972.

Discussion

Combined Action Platoons: The Marines’ ‘Hammer and Anvil’ against the Vietcong

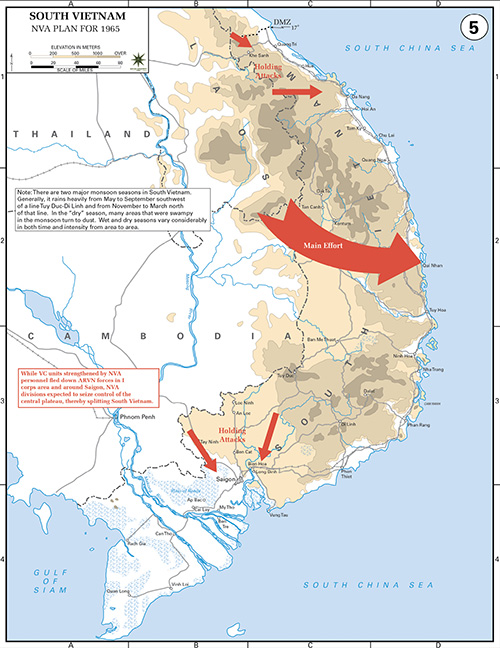

Map courtesy of the United States Military Academy Department of History

Figure 1: The NVA Offensive (1965)3

The Marines of the III Marine Amphibious Force (III MAF) were among the first combat troops deployed to the RVN. The III MAF was subordinated to MACV, which was led by General William Westmoreland in the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon. The USMC occupied the northern part of the country, near the demilitarized zone (DMZ) separating South and North Vietnam. The III MAF commanding officer, General Lewis Walt, expressed his desire to minimize conventional ‘search and destroy’ missions against large Communist units in order to maximize counterinsurgency operations. Counter-guerrilla warfare has always been part of the Marines’ DNA. From the late-19th Century to the Vietnam War, the USMC has seen its units deployed to multiple war zones plagued by insurgencies. Walt was a fervent defender of counterinsurgency and pacification tactics, which sought to gain the support of the civilian population. Although Westmoreland underlined that he adhered to the same principle, he pointed out that he did not have enough troops to carry out a program similar to that of the USMC across South Vietnam; conventional search and destroy operations were more of a priority for him.1 When Westmoreland requested a massive US troop deployment from Washington in the summer of 1965, multiple ARVN battalions were being annihilated by Communist forces who were about to cut South Vietnam in half (see Figure 1).2

The urgency of the situation led to the initiation of major US offensives that aimed to stop the Communist regiments. Notwithstanding, the commanding officer of the Fleet Marine Force in the Pacific, General Viktor Krulak, gave his blessing to General Walt, who authorized the initiation of the Combined Action Platoon (CAP) program in the USMC’s area of operations. The CAPs aimed to ensure the protection of the rural population against insurgents by permanently deploying a squad of 15 Marines with 35 South Vietnamese paramilitary forces to fortified villages. Krulak stated that by denying the insurgents access to the population, the Vietcong would lose its source of survival, as insurgents rely upon civilians for food, recruits and intelligence. Krulak claimed that in the event of a major offensive by large Communist forces, his Marines would be more than capable of confronting them.4 It will be demonstrated later that while the basis of Krulak’s theory was not completely wrong, it had flaws, given the hybrid war context of Vietnam.

CPA Media Pte Ltd/Pictures from History/Alamy Stock Photo 2B00MTB

A South Vietnamese farmer passing a US Marine on patrol, 1965.

In July 1965, the Marines deployed their first CAPs, and in 1969, the program reached its peak with 114 villages and a total force of 2,000 Marines and 3,000 South Vietnamese paramilitary soldiers of the Popular Force (PF).5 It did not take long for Vietcong units to be repeatedly ambushed by the Marines and PF, who severed the insurgents’ lines of communication within village perimeters. As they witnessed the successes of the Marines, civilians began to feel a sense of confidence in the security forces’ ability to protect them. Once they felt genuinely safe, villagers provided intelligence to the Marines regarding Vietcong movements, ambush preparations and booby traps, which facilitated the Marines’ ambush operations and force protection.6 As a logical outcome of this relationship, the villagers and the Marines achieved a perfect symbiosis that facilitated mutual self-protection between peasants and security forces. During an insurgency, the local population would support the group that is most likely to provide them with stability. This is what the Marines provided to the South Vietnamese in the CAP villages. In 1966, living conditions and resources available to the civilian population continued to improve. Within the CAPs, government officials became able to contribute proactively to infrastructure development for rural communities.7 With the Marines’ constant presence, Vietcong insurgents could not operate in the villages as they did before. It was the responsibility of Vietcong political cadres to provide recruits, food, supplies and intelligence to the insurgent combat forces. The actions of the Marines within the CAPs gave a particularly hazardous dimension to this function.8 In addition, observers in the CAP markets prevented the sale of large quantities of rice to potential Vietcong agents, a tactic that made the procurement of food even more complicated for the insurgents. The situation became precarious enough for a captured Vietcong cadre to admit that the Marines had forced his troops to avoid Marine-occupied hamlets, thus forcing them to redirect their operations to non-CAP villages.9

US Library of Congress A185800

A US Marine CAP officer and South Vietnamese paramilitary forces before a strike on a Vietcong stronghold.

Although the system proved effective in a counterinsurgency context, the situation became quite different once conventional military forces came into action. Several CAPs fell into the hands of Communist fighters who fiercely targeted the Marine villages during the Tet Offensive. These assaults, conducted by entire NVA and Vietcong battalions, required the urgent deployment of conventional reinforcements to assist the overwhelmed Marines.10 These assaults proved, beyond any doubt, that an overall battle plan exclusively based on counterinsurgency warfare would have been catastrophic in Vietnam. Small platoon units conducting counterinsurgency are not suited to confront heavily armed battalions supported by artillery and mortar fire. Conventional and counterinsurgency forces had to synchronize their operations if they hoped to counter the Vietcong and NVA modus operandi. The eventual launch of the CORDS program, which introduced a concept similar to CAPs throughout the RVN, encountered similar obstacles when it was launched. However, once conventional MACV units began to coordinate their efforts with those of CORDS, the Vietcong began to show signs of weakness.

ZUMA Press Inc./Alamy Stock Photo ENA1K7

A member of the 1st Cav Div (Airmobile) helps a Vietnamese woman and child across a stream near An Kha, December 1967.

The Rise of CORDS and the Downfall of the Vietcong

CORDS became operational in May 1967 and was put under the leadership of Robert Komer, a member of the US intelligence community who had no superior other than General Westmoreland. CORDS had offices in every province in the country and counted 13,000 military and civilian personnel in its ranks. The program brought under a single umbrella every military and civilian organization charged with carrying out pacification in South Vietnam.11 As with the CAPs, the mission was aimed at conducting civic actions while isolating Communist cadres and insurgents from the population. To this end, paramilitary forces and government cadres of the Revolutionary Development (RD) were deployed to villages and rural areas to facilitate the conduct of local governance. In order to ensure that pacification staff would not be harassed by larger Communist formations, conventional US and ARVN forces were tasked with operating on the periphery of the CORDS areas of responsibility.

Analysis of the first 15 months of the program shows that it had a tough start. The events that unfolded in Cu Chi District epitomize the overall problems that were encountered when CORDS became operational. Before the US deployment of the 25th Infantry Division to Cu Chi District, 10,769 insurgents dominated the area.12 When the 25th Infantry was sent to the district, it initiated a succession of offensive operations, forcing large Vietcong formations to take refuge in isolated areas. This made it easier for paramilitary forces to concentrate on countering local Communist and insurgent cadres in the villages.13 However, when US forces left the district, the Vietcong influence regained momentum. The absence of US conventional troops facilitated Vietcong cadres’ operations. Supported by regular units, they had no difficulty in countering the small paramilitary forces that remained in the villages. MACV or ARVN conventional unit cooperation was essential for CORDS to succeed. An introspective report of the 95th NVA Regiment exposed the disrupting impact US regular forces’ presence had on the NVA’s and Vietcong’s synchronization of operations. For example, the report specifies that the Communists, who controlled 260,000 civilians out of 360,000 in the Phu Yen area, now only controlled 20,000 people. The NVA report attributes this situation to the synchronization of MACV’s conventional and counterinsurgency operations in the area. The plan of action suggested by the Communist leadership was thus to “…crush the pacification plan of the enemy” and repatriate the villagers transferred to the protected villages to their former residences. The report stresses that this was a “life or death situation for the Revolution.”14 It was also reported that the “coordination” between Communist regular and insurgent troops had proven to be dysfunctional, and that the relationship between guerrilla war and regular mobile warfare was not properly exploited.15

ZUMA Press Inc/.Alamy Stock Photo ENA1K4

A medic of the 1st Infantry Division (Airmobile) helps a Vietnamese woman and child flee the Vietcong, 5 May 1967.

The report also criticizes the inability of guerrilla troops to convince the civilian population to turn against the government. It pointed out that in previous years, proselytizing operations aimed at gaining the support of peasants worked very well at the time when troops of the 95th Regiment supported the guerrilla forces.16 The Regiment’s report also mentions the problems generated by the pacification efforts started in the Thon Bac sector. It specified that if the troops of the 95th had managed to remain close to the population by “…increasing the subversive activities” to “weaken and destroy the enemy forces,” the difficulties caused by pacification initiatives could have been countered. Consequently, the NVA’s leadership recommended that troops of the 95th Regiment coordinate their operations with the local guerrilla forces in order to specifically target the pacification initiatives in the Thon Bac region.17 When the 25th US Division left Cu Chi without leaving a single battalion in the area, insurgents were able to follow a course of action similar to what was suggested in the NVA 95th Regiment’s report. CORDS staff encountered the same obstacles in almost every South Vietnamese province. However, during the Communists’ Tet offensive in 1968, the Vietcong suffered catastrophic losses, allowing CORDS to seize the initiative. About half of the 84,000 Communists deployed for Tet were neutralized. In addition, subsequent Communist spring offensives, dubbed “mini-Tet,” inflicted heavy casualties on the Vietcong: around 1,000 Communists defected, and 5,000 insurgents and NVA soldiers were killed in action on a weekly basis. The attrition caused to the Vietcong’s political infrastructure also resulted in the loss of several hundred cadres.18

Robert Komer undertook a genuine bureaucratic battle that aimed to force military planners to pay more attention to pacification forces. He insisted that conventional forces had to synchronize their combat operations against large Communist formations so as to facilitate the task of the government’s paramilitary units in the rural areas. South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu also instructed that each village should have its RD cadres and defensive forces on a permanent basis.19 Like Komer, Thieu insisted that ARVN commanders conduct conventional operations in conjunction with counterinsurgency initiatives. His aim was to systematically secure one area and move on to the next in order to geographically expand pacification and government control of rural sectors. This course of action, launched in November 1968, was to become the Accelerated Pacification Campaign (APC),20 which was executed alongside CORDS. Moreover, in June 1968, General Westmoreland was replaced at the head of MACV by General Creighton Abrams. The latter was a staunch defender of counter-guerilla warfare, and believed in the need to combine conventional and counterinsurgency operations. Abrams set in motion a battle plan in which conventional forces would track down and eliminate large Communist formations; at the same time, small unit operations, including patrols and ambushes against Vietcong guerilla units would be initiated.21 The pressure put on Vietcong forces gradually increased over the following months. Then, following a new insurgent offensive during Tet 1969, Communist losses were so catastrophic that the Vietcong headquarters, led by the Central Office for South Vietnam (COSVN), issued an order that put an end to conventional military operations for the guerrillas. The COSVN wished to concentrate its efforts on subversive and influence operations targeting the civilian population, while maximizing the mission of its political cadres and small guerrilla forces.22

However, the losses inflicted on the insurgents during the fighting galvanized CORDS’ momentum. In the summer of 1969, security around the Mekong Delta, in the south of the country, was improved to such an extent that it was possible to travel unescorted during daytime from one provincial capital to another. Each hamlet now benefited from the protection of a platoon of paramilitary forces assisted by village militias. Considering that most small guerilla units did not benefit from the support of larger Communist forces anymore, the military capabilities and political influence of the insurgents were grievously hampered.23 Progress in pacification was not limited to the south of the country. Across the RVN as a whole, control of Communist cadres over the rural population collapsed to 12.3%, then to 3%. Protected peasants cultivated 5.1 million tonnes of rice without the Vietcong being able to benefit from it. About 47,000 Communist soldiers and cadres joined the South Vietnamese ranks through the Chieu Hoi amnesty and defector program.29 In 1967, 400,000 civilians were forced to leave their villages due to combat operations. In 1969, the number of refugees fell to 114,000 for the entire country.24

Amalgamated to CORDS was a Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) initiative called the Phoenix program, which was also meant to drastically exacerbate the already precarious situation of the insurgency. For decades, Phoenix had a poor reputation because it was unjustly labelled an assassination program. Fortunately, authors like Mike Moyar (Phoenix and the Birds of Prey: Counterinsurgency and Counterterrorism in Vietnam) and Phoenix veteran Lieutenant Colonel John Cook (The Advisor: The Phoenix Program in Vietnam) both set the record straight regarding Phoenix in Vietnam. Declassified Communist reports also expose Phoenix’s effectiveness against the insurgency. In many ways, the program was a precursor to what the Joint Special Operations Command executed in Iraq when US and British Special Forces crippled Al-Qaeda’s leadership network between 2005 and 2011. Phoenix was launched in December 1967 and aimed to eliminate the Vietcong Infrastructure (VCI). VCI members constituted the political and administrative organs of the insurgency. They were supported by security forces that ensured their protection and cadres in charge of finances and taxation, as well as other members whose mandate consisted of ensuring the management and control of the civilian population.25 The task of neutralizing VCI members fell to US Navy SEALs, South Vietnamese Special Forces of the Provincial Reconnaissance Unit (PRU), RD cadres and constabulary and paramilitary forces. By recruiting multiple informants in villages and through human intelligence collected from numerous Vietcong defectors, Phoenix operators caused catastrophic damage to an already crippled insurgency. In 1967, about 80,000 Communist cadres were operating in areas still under Vietcong influence.26 In the first 11 months of 1968, Phoenix neutralized 13,404 cadres. In November 1968 alone, 366 cadres defected, 1,563 others were taken prisoner and 409 more were killed during operations aimed at their capture.27 In Quang Tri Province, PRU actions caused such damage to the VCI that the Communists deployed a special commando unit to destroy a PRU operating base.28 A COSVN document complained about the significant damage inflicted on them by the PRUs and the Chieu Hoi defector program. Other seized Communist documents and interrogation reports attest that in many areas, the morale of Vietcong cadres was “extremely low.” The rate of VCI defection increased by 49% in the second half of 1968. Communist reports also indicated that a significant number of cadres were unable to operate freely within their area of responsibility, even after dark. The attrition rate inflicted by Phoenix on VCI members forced the COSVN to deploy new young, inexperienced cadres, totally lacking their predecessors’ expertise. In several cases, a single cadre was assigned responsibilities normally allotted to two or three of his peers.30

Phoenix administrators attributed much of the operational success to the cooperation between MACV regular forces and intelligence corps with those dedicated to Phoenix operations.31 It was also observed that Phoenix and regular force operations against the Vietcong and its political infrastructure encouraged the rural population to cease their collaboration with the insurgents.32 In 1969, 19,534 more cadres were neutralized due to Phoenix.33 Although Phoenix figures are known not to be 100% accurate (many Vietcong guerillas were mistakenly designated as VCI), the attrition caused to the VCI was reflected in COSVN reports, the drastic drop in insurgent recruitment activities, and the testimony of Communist defectors. A VCI deserter admitted that the Vietcong feared Phoenix, which was trying to “…destroy its organizations” and denied its cadres access to the civilian population.34 He also stated that insurgents who did not have to deal with villagers received very specific instructions from Vietcong leadership: contacts with the population were prohibited, due to the overwhelming presence and influence of Phoenix agents in rural areas. The defector also said that Vietcong commanders warned their subordinates that Phoenix was “…a very dangerous organization” of the South Vietnamese pacification program.35 Another communist report bemoaned the ability of Phoenix agents to target cadres, noting that the program’s members were “…the most dangerous enemies of the Revolution.” The same report insists that no organization other than Phoenix could cause the Communist struggle so many problems and difficulties. The North Vietnamese leader, Ho Chi Minh, himself admitted that he was “much more worried” about the US forces’ successes against the VCI than those obtained against the NVA.36 When peace talks began between Washington and Hanoi in Paris, Communist officials demanded the cessation of all operations related to the Phoenix program.37

In July 1969, the COSVN published Resolution 9 for its members in order to counter the negative effects of the MACV’s counterinsurgency campaign. The Resolution ordered guerilla forces to focus their targeting operations upon pacification personnel in rural areas. A few months later, confronted with its subordinates’ inability to follow the directives of Resolution 9, the COSVN published Resolution 14, which insisted again on the need to revert to a guerrilla warfare concept in order to overcome the enemy’s pacification program. It also criticized the slowness of guerrilla force movements, as well as the low level of progress in regaining control of rural areas. In addition, Resolution 14 denounced the Party Committees’ and military commanders’ failure to increase pressure on counterinsurgency forces, as well as their failure to gain the civilian population’s support in sectors deemed more vulnerable.38 Other seized documents exposed the Communists’ growing loss of control of rural areas. Vietcong Party Committee members in charge of the region surrounding Saigon claimed that “revolutionary forces” were under a lot of pressure, a consequence of the loss of senior cadres in the districts, as well as of the anemic population pool still accessible for recruitment. They also criticized Communist units’ inability to achieve a major victory. The Committee admitted that their forces were “poor in quality and quantity,” and unable to establish contact with the population. Also mentioned were the incapacity of large combat formations to operate near populated areas, and local guerillas’ ineffectiveness in their attempts to convince the population to support their operations. Vietcong leadership further stated that guerrilla forces “continue to suffer losses,” and remained unable to renew their strength. Political groups aimed at indoctrinating civilians were labelled “weak,” small and “incompetent.” The Committee recognized the control exerted by government forces over the civilian population while criticizing the inability of Communist forces to reverse the situation.39 CORDS analysts observed that from 1968 to 1970, terrorist incidents related to Vietcong activities continued to drop. The same was true for the number of civilians killed, injured, or abducted by insurgents.40

William Colby, former Saigon CIA station chief, appointed as successor to Komer at the head of CORDS, explained that regular troops managed to drive large Communist formations away from rural areas, which supported the pacification program’s progress. By the beginning of 1970, most pacification objectives had been achieved, with 90% of the population living in hamlets enjoying acceptable security, and 50% living in areas considered “completely secure.”41 During rural elections in 1970, 97% of populated areas were able to vote freely without Vietcong interference.42 In 1971, terrorist acts declined by 75% in more secure areas, and by 50% in areas classified as less secure.43 The inaccessibility of the population, the rate of desertions, and the inability to operate freely in the country drastically hampered the Vietcong’s ability to remain combat effective. At this point, in most of the insurgency’s areas of responsibility in South Vietnam, 70% to 80% of the remaining Vietcong units were, in fact, made up of regular NVA soldiers.44

From Hybrid to Conventional Warfare: The NVA’s Military Victory in South Vietnam

In 1972, the North Vietnamese regular forces, far from being decimated like the Vietcong, took charge of military operations and launched the “Spring Offensive,” a major multi-divisional campaign aimed at destroying the ARVN and regaining the initiative following US combat forces’ departure from South Vietnam. Multiple NVA divisions supported by Soviet-supplied tanks and artillery invaded the South via the DMZ and Laos while several more divisions, dispatched from Cambodia, invaded the southern parts of the country. This offensive marked the end of the Vietnam War as a hybrid conflict as the NVA relied exclusively on conventional warfare tactics. Two NVA divisions took control of three districts in the centre of South Vietnam, which like in 1965, was on the verge of being cut in half.45

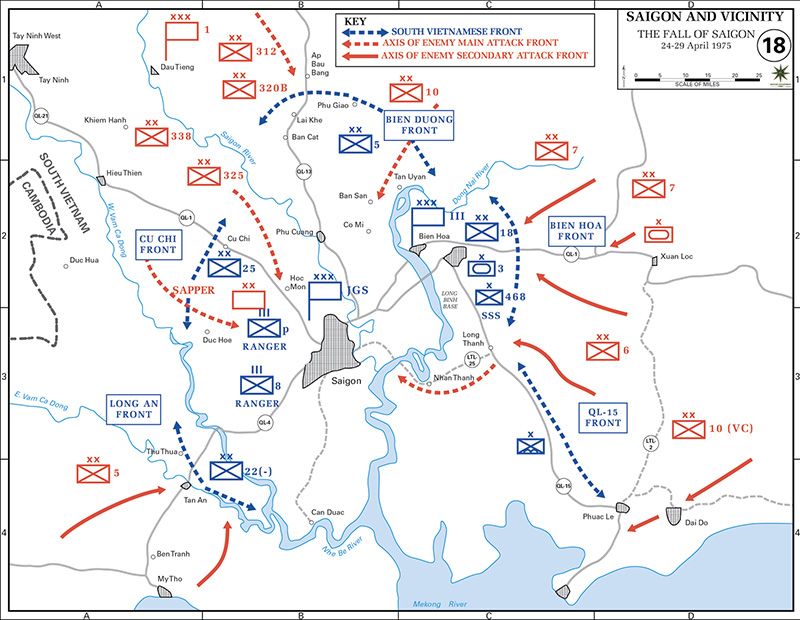

Map courtesy of the United States Military Academy Department of History

Figure 2: The NVA’s Final Invasion of South Vietnam46

However, NVA regiments suffered massive casualties as they were pushed back by ARVN divisions supported by US advisors and B-52 bombers.47 In order to stop the NVA, B-52s conducted 4,759 bombing missions. Approximately 400 tanks were destroyed, and about 48,000 NVA soldiers were killed in action (only 10,000 fewer than all US casualties for the whole war).48 General Abrams stated that without the B-52s, it would have been impossible to stop the NVA. However, he also mentioned that the B-52s would not have been enough if the ARVN had not stood its ground against the NVA.49 At that point in the war, the military threat was of a conventional nature, and it required a South Vietnamese Army ready to fight using classic defensive and offensive military tactics if it was to successfully counter the next Communist offensive.

ZUMA Press Inc./Alamy Stock Photo ENA4C

A pair of riflemen of the 173rd Airborne Brigade charge toward Vietcong positions in a wooded area in War Zone “D.”

Military hostilities subsequent to the Spring Offensive did not involve much of what remained of the Vietcong, whose actual impact upon the battlefield became sporadic. The once-powerful insurgency was to assume no significant role in what was to bring about the fall of South Vietnam. Three years were enough for Hanoi to rebuild its forces following the scathing defeat of 1972. In the spring of 1975, the NVA launched a new multi-divisional campaign in the RVN. The entire country was attacked via multiple fronts by several NVA divisions in a blitzkrieg-style offensive, with infantry supported by tanks and artillery (Figs 2 & 3). ARVN forces were outflanked and consistently retreated despite all the training and weaponry the Americans provided to the South Vietnamese soldiers.

Map courtesy of the United States Military Academy Department of History

Figure 3: The NVA’s Offensive on Saigon50

During the hostilities, NVA soldiers proved they were superior fighters to their South Vietnamese counterparts once the latter were deprived of US air support. On this occasion, no B-52s or US advisors were sent to assist the ARVN, which saw each of its regiments systematically wiped out by North Vietnamese units. Even though US President Gerald Ford expressed the will to order the deployment of B-52s to stop the Communist invasion, the United States Congress, which sought to reaffirm its powers, opposed the President’s request, thereby leaving South Vietnam to its fate.51 While the Vietcong insurgency was effectively defeated, the NVA remained operational and well supplied, which allowed its forces to invade South Vietnam and best the ARVN in combat.

CPA Media Pte Ltd./Pictures from History/Alamy Stock Photo 2B01CCF

The capture of Saigon, 30 April 1975.

Conclusion

Close examination of tactical military operations in Vietnam clearly exposes the following facts: first, the Communists’ modus operandi in Vietnam entirely justified MACV’s concept of operations, which, aside from counterinsurgency, exploited conventional military doctrine to counter NVA and larger Vietcong units. The NVA maximized conventional warfare doctrine, while the Vietcong used both conventional and guerrilla tactics, thus requiring a symmetric US and South Vietnamese military response. A military campaign exclusively set upon counterinsurgency would have been a catastrophe, as was demonstrated with the Marines’ CAPs. As effective as they were in a guerilla war context, CAPs showed great vulnerability when confronted by regular Communist regiments. The same can be said of the CORDS program at its beginnings: the presence of large Communist units proved far too difficult to manage for small platoons tasked with counterinsurgency operations. This is why it remained critical for MACV and South Vietnamese regular forces to synchronize their conventional military operations with counterinsurgency initiatives, a situation that was corrected under the leadership of General Creighton Abrams and Nguyen Van Thieu’s APC.

Second, while it took time and adjustments, the US military demonstrated tremendous ability in exercising counterinsurgency in Vietnam. Declassified Communist documents expose the extent of the Communist leadership’s grievances regarding the devastating effects the CORDS and Phoenix programs had on the VCI. The latter, as well as Vietcong troops, defected by the tens of thousands, and Communist cadres lost most of their grip on rural South Vietnam. Although the insurgency was ultimately neutralized and mainly composed of NVA soldiers in 1971, Hanoi’s hybrid warfare strategy also relied on its conventional forces of the NVA, which leads us to the third and final fact: in the end, it was NVA regular battalions, not the Vietcong, who overran ARVN forces on the battlefield. In 1972, when the NVA took over Communist military operations, the conflict morphed into a conventional war. MACV’s ability to neutralize the insurgency was simply not enough, given the NVA’s continuous presence on the battlefield. In the end, the NVA managed to defeat the ARVN and bring about the fall of South Vietnam in April 1975. Paradoxically, it was the US forces’ inability to neutralize the Communists’ regular army, as well as the ARVN’s lack of proficiency in conventional warfare that brought about the South’s military defeat, not “bad counterinsurgency,” or “overreliance” upon conventional tactics.

In retrospect, much is still to be learned from the American experience in Vietnam. One of the biggest post-war blunders of the US military was to put aside everything they learned through their experience in developing and executing their counterinsurgency program in a hybrid warfare environment. After the war, the Pentagon undertook a series of reforms to reinvigorate its armed forces. This restructuring was enabled through the Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC). Analysis of TRADOC’s post-war training program and Army field manuals unambiguously exposes the military’s tendency to focus its attention almost solely on conventional warfare while all aspects related to counterinsurgency and hybrid warfare were basically ignored. Rather than providing feedback on counterinsurgency and hybrid operations in Vietnam, TRADOC preferred to revitalize its conventional doctrine by drawing on lessons learned by the Israeli Army during the Yom Kippur War.52 US military leadership, completely saturated by the Vietnam War, seemed determined to forget all it had learned, through sweat and blood, when it conceptualized its counterinsurgency strategy in South Vietnam.

Third, when US forces were confronted by a violent insurgency in Iraq in 2003, they had to go back to the basics of counterinsurgency. The US military thus needed to relearn what it had unlearned, which cost the lives of thousands of Americans and Iraqis on the battlefield. This tendency is not unique to the US military: when Canadian forces came back from Afghanistan, the same dynamic was observed as the focus of military training was set upon conventional warfare, while the hard counterinsurgency lessons learned on the Afghan battlefield were mostly set aside. Modern armies are bred to conduct conventional warfare, and hence, have a duty to hone their soldiers’ skills in that regard. However, this should never be done at the expense of knowledge acquired through arduous counterinsurgency military campaigns. The fact that hybrid warfare is a phenomenon on the rise in the 21st Century brings credence to this assertion, thus making the Vietnam experience a real treasure trove of lessons learned for all modern military forces anxious to be ready for the next war.

CPA Media Pte Ltd./Pictures from History/Alamy Stock Photo 2B00WBH

South Vietnamese refugees fleeing the communist conquest of Saigon in 1975 arrive at Camp Foster, Okinawa, Japan.

Notes

- USMC Records/Headquarters Marine Corps History and Museum Division. Background and Draft Material for U.S. Marines in Vietnam. College Park, National Archives, RG#127, Entry A-1(1085), Box 23, p. 1.

- Pentagon Papers. Part IV. C. 5[Part IV. C. 5.] Evolution of the War. Direct Action: The Johnson Commitments, 1964-1968. College Park National Archives Identifier: 5890504, Container ID: 4, p. 3.

- US Military Academy West Point, Maps and Atlases, Vietnam War “NVA Plan for 1965.”

- William R. Corson. The Betrayal. New York, Norton & Company, 1968, p. 184.

- Ibid.

- USMC Records/Headquarters Marine Corps History and Museum Division. Modification to the III MAF Combined Action Program in the RVN. College Park, National Archives, NND 9841145, RG#127, Box 119, p. C-9-C-10.

- Ibid., p. C-12-C-14.

- USMC Records/History and Museum Division. III MAF. Marine Combined Action Program in Vietnam by Lt Col W.R. Corson USMC. College Park, National Archives, NND 984145, RG#127, Box 152, pp. 14-15.

- Ibid., p. 186.

- Michael E. Peterson. The Combined Action Platoons. New York, Praeger, 1989, pp. 56-58.

- Records of the US Forces in Southeast Asia/Headquarters, MACV Office of CORDS Pacification Studies Group. General Records US Weekly Returnee Reports 1969 thru Plans/1970. College Park, National Archives, NND 45603, RG#472, Box 7.

- Records of the US Forces in Southeast Asia/Headquarters, MACV Office of CORDS Pacification Studies Group. General Records 1601-04 USAID/CORD Spring Review PSG 64/70 1970 thru 1601-10A. College Park, National Archives, NND 994025, RG#472, Box 8, pp. 1-2, 10-11.

- Records of the US Forces in Southeast Asia/Headquarters, MACV Office of CORDS Pacification Studies Group. General Records US Weekly Returnee Reports 1969 thru Plans/1970/Supplements, op. cit.

- U.S. Army Military History Institute. Vietnam Documents and Research Notes Series Translation and Analysis of Significant Viet-Cong/North Vietnamese Documents, Problems of a North Vietnamese Regiment. Carlisle, War College, ProQuest Folder: 003233-001-0131, p. 26.

- Ibid., p. 4.

- Ibid., p. 11.

- Ibid., pp. 14-15.

- Thomas Ahern. Vietnam Declassified. Lexington, University Press of Kentucky, 2010, p. 306.

- Stephen Young. The Theory and Practice of Associative Power. Lanham, Hamilton Books, 2017, pp. 128-129.

- Ibid.

- Lewis Sorley. Vietnam Chronicles The Abrams Tapes 1968-1972. Lubbock, Texas Tech University Press, 2004, p. xix.

- Records of the US Forces in Southeast Asia, MACV Office of CORDS, MR 1 Phuong Hoang Division. General Records 1603-03A: PRU Correspondence: Reports – VIETCONG/NVN Propaganda Analysis 1970. College Park, National Archives, NND 974306, RG#472, Box 12, p. 1.

- Ibid., pp. 163-164.

- Ibid., p. 180.

- Ibid.

- Records of the US Forces in Southeast Asia, MACV Office of CORDS, MR 2 Phuong Hoang Division. General Record Operation Phung Hoang Rooting Out the Communists’ Shadow Government. College Park, National Archives, NND 974306, RG#472, Entry: 33104, Box 4, p. 2.

- Ibid.

- Andrew Finlayson. Marine Advisors With the Vietnamese PRU, 1966-1970. Quantico, USMC History Division, 2009, pp. 15-16.

- U.S. Army Military Institute. Translation and Analysis of Significant Viet-Cong/North Vietnamese Documents, A COSVN Directive for Eliminating Contacts With Puppet Personnel and Other “Complex Problems.” Carlisle, War College, ProQuest Folder: 003233-001-0731, p. 3.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Records of the US Forces in Southeast Asia/Headquarters, MACV Office of CORDS Pacification Studies Group. General Records Phung Hoang 1968 thru Vietnamization/C/S Letter 1969. College Park, National Archives, NND 003062, RG#472, Entry: PSG, Box 3, pp. 7-8.

- Records of the US Forces in Southeast Asia, MACV Office of CORDS, MR 2 Phuong Hoang Division. General Records 1602-08: US/GVN Insp. Team Visits, Jul-Dec 1970. College Park, National Archives, NND 974305, RG# 472, Entry 33104, Box 7, p. 2.

- Ibid.

- Finlayson, op. cit., pp. 27.

- Records of the US Forces in Southeast Asia, MACV Office of CORDS, MR 2 Phuong Hoang Division. General Records 207-01: Reorganisation 1970. College Park, National Archives, NND 974306, RG#472, Entry: 33205, Box 5, p. 1.

- U.S. Army Military Institute. Translation and Analysis of Significant Viet-Cong/North Vietnamese Documents. A preliminary report on activities during the 1969 Autumn Campaign. Carlisle, War College, Pro Quest Folder: 003233-001-0741, p. 1.

- Ibid., pp.1-2, 6-7.

- Records of the US Forces in Southeast Asia/Headquarters, MACV Office of CORDS Pacification Studies Group. General Records 1601-10A IV Corps/Phong Dinh/Trip Report 1970. College Park, National Archives, NND 994025, RG#472, Box 9.

- Historical Division Joint Secretariat JCS. The Joint Chiefs of Staff and the War in Vietnam, 1969-1970. Washington, Historical Division Joint Secretariat JCS, July 1, 1970, pp. 431-432.

- Ibid., p. 448.

- Ibid., pp. 222-225.

- Ibid., pp. 1-2.

- Young, op. cit., pp. 236-239.

- US Military Academy West Point, Maps and Atlases, Vietnam War “The Final Days.”

- Ibid., p. 239.

- Sorley, op. cit., pp. 872-873.

- Young, op. cit., pp. 244-245.

- US Military Academy West Point, Maps and Atlases, Vietnam War “The Fall of Saigon.”

- Robert R. Tomes. US Defense Strategy from Vietnam to Operation Iraqi Freedom. New York, Routledge, 2007, p. 54.

- Combat Studies Institute. Selected Papers of General William E. Depuy. Fort Leavenworth, Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC), 1973, pp. 70-71.