Image by: S1 Lisa Sheppard, Military Photojournalist, RMC

First day of classes for the Naval and Officer Cadets from RMC, September 06, 2022.

Stéphanie Chouinard is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Royal Military College (Kingston), cross-appointed at Queen's University. She is a Fellow of the Pierre Elliott Trudeau Foundation.

Holly Ann Garnett is an Associate Professor of Political Science at the Royal Military College, cross-appointed to the Department of Political Studies and School of Policy Studies at Queen's University, and co-director of the Electoral Integrity Project.

Introduction

This article studies the political attitudes of officer cadets and naval cadets (OCdts and NCdts, respectively) at the Royal Military College (RMC). We know that political attitudesFootnote 1 shape leadership style and behaviour in an increasingly diverse Canadian Armed Forces.Footnote 2 These cadets will soon be responsible for members of the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF), some of whom will be young adults themselves, possibly imprinting their political attitudes on their subordinate troops. It is therefore particularly relevant to measure this population since they will eventually be in positions of authority in the military hierarchy.

Concurrently, young adulthood is a crucial time in one’s life for political socialization. Those years are widely considered to be “the impressionable years”;Footnote 3 that is to say, the moment in individuals’ lives where sociopolitical attitudes not only change the most, but also eventually crystallize for the rest of adulthood.Footnote 4 Postsecondary enrollment in particular has long been shown to have an important effect on political attitudes, notably through processes of peer-based normative influence.Footnote 5

Research has also shown that the military as an institution fosters a specific culture, leading to political attitudes among its members that are different than that of the society it is meant to serve and protect.Footnote 6 However, in recent years this gap has appeared to narrow.Footnote 7 Our literature review will show that while this civilian-military gap has been studied to an extent in the American context, recent research on this topic is lacking in Canada.

This article, then, aims to fill a gap in the literature on civilian-military attitudinal differences by shedding light on Canadian OCdts and NCdts’ political behaviours and attitudes towards civic life. Through surveys administered at RMC in the context of a course from the core curriculum, POE/F 205: Canadian Politics and Society/Société et politique canadiennes, we measured several cohorts of cadets’ attitudes towards politically salient issues relating to democracy and civic life and considered how their attitudes compare to civilian citizens’. We chose this course to populate our survey because it allowed us to have the largest possible number of participants of all the courses offered in our department, as all OCdts and NCdts enrolled in all programs offered at RMC must take it over the course of their studies.

This article first outlines the literature on political socialization and how attitudes and behaviours towards political life develop, particularly around the college years. It also highlights the role that military education may play in shaping military members’ worldviews, as well as whether a “socialization gap” between civilians and military members still exists, resulting in different political attitudes among the two groups. Next, the article provides a summary of the survey activity. It will then present summary results, comparing the cadet population to the general Canadian population and its peer group. It concludes with a discussion providing important insights into the attitudes of Canada’s new generation of military officers and a discussion on the significance of our results for military education and civil-military relations in Canada writ large.

Literature

The formation of political attitudes and attitudinal change in young adults

The question of how individuals’ political attitudes form, whether they can change over time, and if so, how, has long been occupying the minds of political scientists in the flourishing literature on this topic over the past 60 years. One of the key variables identified in this process early on by researchers has been age, and more specifically the relationship between age and openness to change. Indeed, the attitudes of older people are demonstrably more stable than those of younger people.Footnote 8

However, this observation alone does not explain why younger people’s attitudes appear to be more malleable. There are at least two plausible explanations. The first posits that younger people may be more easily impressionable, because of a lack of life experience.Footnote 9 Alternatively, age may not really be the important factor, but rather one’s lifestyle. More recent research suggests that the experiences younger people face provide them with more opportunities to reconsider their opinions and attitudes than they will have later in life.Footnote 10 In other words, it’s not that older people are incapable of attitudinal change, but rather that they are not faced with situations that allow them to reconsider their prior beliefs often as they get older.Footnote 11

The importance of postsecondary enrollment in attitudinal change

In both scenarios, postsecondary enrollment is considered an important event in attitudinal formation and change. The age at which most individuals will enter college or university is concordant with the age of their official political maturation as full citizens.Footnote 12 As they gain the right to vote, they likely have a heightened sense of political awareness. This new civic responsibility may foster a greater “political vulnerability” at that specific age which makes individuals more receptive to new ideas.Footnote 13 Postsecondary education thus becomes an important milestone for attitudinal change, through the confrontation between the values and beliefs held at home, which have been “in part idealized in childhood,”Footnote 14 and new ideas to which students are exposed, either formally in the classroom environment, or less formally, through their peers. Postsecondary education may be so important an experience for political socialization that according to some research, it could be the one factor that explains why so much change takes place between the ages of 18 and 25.Footnote 15 Moreover, attitudinal change during college years appears to be long-lasting in nature, crystallizing into one’s adulthood, making it a milestone of paramount significance.Footnote 16

Image by: Avr Makala Rose, Imagery Technician, OJE, RMC, Kingston 2022-RMC2-0115

Naval and Officer Cadets participate in the Royal Military College (RMC) obstacle course to mark the end of this year’s First Year Orientation Program (FYOP). RMC Grounds, RMC, Kingston, ON September 23, 2022.

From the processes at play in the postsecondary experience, the literature stresses the role of “normative influence,” or “group identification” as having a great impact on attitudinal change. In other words, the influence of peer groups is seen as highly relevant in understanding how change occurs during those years: “Students […] change their social and political views to conform to standards set by their peers, the change being motivated presumably by a desire for acceptance and social approval — the need to be liked.”Footnote 17 However, an alternative explanation can also be offered: that students’ attitudes would change through their academic program, “because of the information to which they are exposed, and their motivation would [rather] be a concern for being right.”Footnote 18 It has also been shown that smaller college settings, such as the one found at RMC, tend to produce a college experience that as a whole outweighs the influence of a specific program, and create stronger cohesiveness among a given cohort.Footnote 19

Political attitudes among military students

By way of comparison, students enrolled in U.S. military colleges tend to hold more socio-politically conservative views than their peers enrolled in civilian universities.Footnote 20 For example, American research from 2001 demonstrated that West Point students were more “conservative, patriotic, and warrioristic,” than their civilian peers at the time.Footnote 21 Military students have also demonstrated higher levels of authoritarianism than civilian peers in the past, for example when asked their opinions about convicts and ex-convicts.Footnote 22 A more recent study on attitudes towards the issue of homosexual serve in the American military found that military academy students were more likely to agree with the barring of homosexuals from military service, followed by ROTP students, and then civilian students.Footnote 23

However, there remain questions whether this gap in attitudes found in the American context is related to pre-existing attitudes or the process of socialization. For example, recent research indicates no significant differences between military and civilian students upon enrollment on the measurement of two indicators: right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation. These indicators have been associated in other studies as indices of political conservatism and negative prejudices towards certain nondominant groups in society.Footnote 24 According to Nicol, Charbonneau and Boies (2007), students who elect to attend a military college are, at the onset of their studies, no different than their civilian peers on these two measures, but eventually score higher for social dominance. The authors posit that the process of military socialization, rather than pre-existing political beliefs, is what fosters more conservative attitudes in military members.Footnote 25 The result of this process is what we commonly call the “military-civilian gap,” where the attitudes of members of the military do not reflect those of the civilians they are meant to serve and protect.Footnote 26

These results once again highlight the significance of the college experience on political socialization. By focusing on only two measures of these students’ attitudes, however, this recent study only gives us a narrow glimpse into their political beliefs. For example, how satisfied are they with our democracy or our other Canadian political institutions? How much trust do they place in our elected representatives? Does this affect their civic engagement? And how do they compare with their civilian peers, as well as the Canadian population writ large, on these issues?

The issue of political attitudes of members of the armed forces, in Canada and abroad, has always been crucial, as this is a population we trust with the protection of the sovereignty of the state, which involves, among other things, the manipulation of lethal weapons. In Canada these questions, which have preoccupied researchers and the public writ large in the past following the “Somalia incident”Footnote 27 for example, are once again gaining salience in recent years. According to some observers, what can be considered a weak civilian oversight of the military in CanadaFootnote 28 has led, among other things, to the development of troubling attitudes among officers and members of the rank. Instances of systemic racism and discrimination, gender bias, sexual misconduct, and white supremacy and right-wing extremismFootnote 29 in the CAF have recently come to light, raising once again questions about the military-civilian gap in political attitudes in Canada and the erosion of public trust in the CAF.

Research Questions & Hypotheses

We are interested to know the attitudes of Canadian OCdts and NCdts towards civic life and how these compare with their civilian counterparts. To do so, we look at a number of key indicators of an individual’s core political beliefs and behaviours.

Considering first fundamental opinions towards democratic politics and community, we compare how RMC students’ generalized trust differs from the general population and their age cohort peer group. Generalized trust is a key indicator of social capital, and refers to feelings of reciprocity within the networks that make up the fabric of our democratic society.Footnote 30 This attitude has been known to affect many other political attitudes and behaviours, from political participationFootnote 3 to violent crime.Footnote 32 CAF members are required to have a greater level of trust in their colleagues than in most workplaces. At the same time, they are also trained to keep a careful eye on potentially difficult social and political situations. Nonetheless, because generalized trust is such a fundamental attitude, we predict that due to self-selection into the CAF among those most likely to have higher levels of feelings of civic community, we expect generalized trust to be higher among RMC students.

Image by: Avr Makala Rose, Imagery Technician, OJE, RMC, Kingston.

Naval and Officer Cadets participate in RMC’s obstacle course to mark the end of FYOP. September 23, 2022.

Next, we ask: Do RMC students differ from the general population and their peer group for satisfaction with democracy? Satisfaction with democracy has been theorized to measure both (or either) aspirational perceptions of the concept of democracy, but also the reality of how a democratic regime is working or political support.Footnote 33 We anticipate that RMC students, by the self-selection into the CAF where they are serving the democratic regime, may have greater satisfaction with democracy. Just as popular support for democracy is important for the health of a democratic regime, it is possible that support for democracy within this cohort of young cadets will be important to the health of the CAF.

Turning to more concrete political attitudes, we are interested in knowing RMC students’ interest in politics and general feelings towards politicians and political life as it functions in Canada. Regarding feelings towards political actors, we do not expect to see much difference between RMC students and their peer groups. Their self-selection into military life or military training should not have a major influence on feelings towards politicians and political campaigns. Conversely, we expect that interest in politics may be affected though RMC training, as students are required to take a core curriculum that includes social sciences and humanities, including politics and history. Exposure to these subjects may improve RMC students’ interest in politics beyond their peer group.

Finally, we are interested to know whether these attitudes and beliefs of RMC students translate into different patterns of political behaviours and civic engagement. Considering voter turnout, we expect that although youth are generally the least likely to vote, RMC cadets may be more likely to participate in politics through the traditional means of voting due to an awareness that elected government officials, through civilian oversight of the military, have a concrete impact on their day-to-day life in the CAF. We also expect higher rates of civic engagement through volunteerism, due to the self-selected or indoctrinated sense of community responsibility which is one of the core values of the CAF.

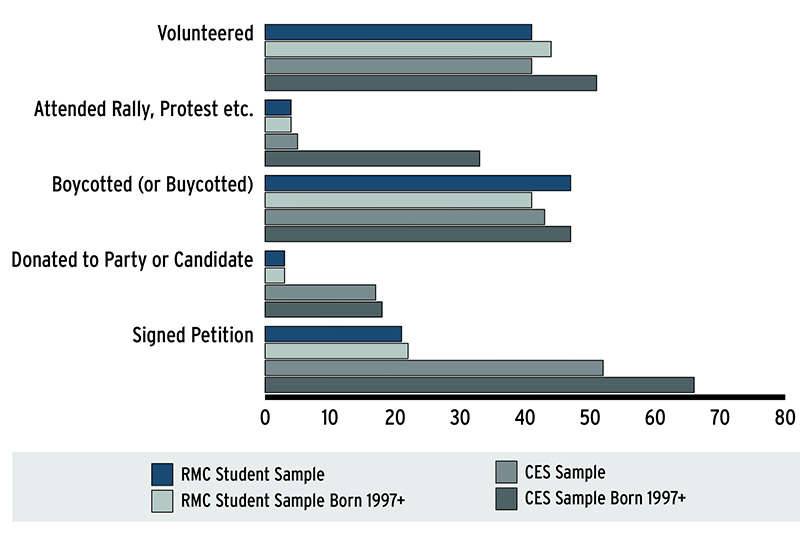

However, we know that some forms of political participation are unavailable to RMC students and all CAF members. For example, their terms of engagement explicitly state they are not to participate openly in partisan political activitiesFootnote 34 or in some cases sign petitions.Footnote 35 Thus, these political activities should be lower among RMC students than the general population.

Method

To respond to these research questions, we undertook a survey of students at RMC in the mandatory POE/F 205 (Canadian Politics and Society/Politique et société canadiennes) course in the 2019–2020 and 2020–2021 academic years. As part of the core curriculum, this course provided us an opportunity to survey a broad cross-section of the student population at RMC. StudentsFootnote 36 enrolled in this course took two surveys, though the focus of the present research is the first survey that establishes baselines of political attitudes. The survey was administered in-person (paper) in 2019–2020 and online in 2020–2022 (due to pandemic constraints), however it was the same survey administered. This resulted in 503 attempted surveys: 239 from 2020, 200 from 2021 and 64 for 2022. The decline in responses in the final year was due to fewer professors administering the survey to their students. Response rates for single questions vary since students had the option of skipping any question or terminating the survey at any point in time. Of the 473 respondents who chose to answer their gender, 75% were male and 24% were female; the remaining 1% responded “other”.

The survey utilized question wording from the 2015 Canadian Election Study (CES)Footnote 37 to allow for comparisons against a broader representative sample of the Canadian population and cover basic socio-demographic variables and attitudes about Canadian politics. Thus, to compare the students with the general population, we employ the data from the 2019 CES. This nationally representative survey is conducted during and after every federal election in Canada, and the individual-level data are (minus identifiers) available openly to the public. The 2019 study, run by the Consortium for Electoral Democracy, included both a phone and an Internet sample.Footnote 38 Although survey weights are available, we did not weigh these data in our analysis. The entire sample from the 2019 CES consists of over 37,000 respondents over multiple waves and survey modes. In most cases, however, an individual question was only answered by a portion of these respondents.

To compare the student population with their peer group in the general population, we compare with those born between 1997–2001 from the CES, which results in 2,019 respondents, though again the exact number to have responded to any particular question is much smaller. We likewise also present the results only for the subset of the RMC student data who are also born between 1997 and 2001, recognizing that there may be fundamental differences between younger students and their older counterparts. Thus, the results consider four major groups:

- The full RMC sample

- The RMC sample born between 1997–2001

- The full Canadian population sample

- The Canada population sample born between 1997–2001

A final note on the methodology employed — we do not ascribe causality in any way to any differences noted. We believe that the student population that elects to attend RMC may be significantly different, having different motivations and goals for pursuing a career in the CAF. Thus, we are careful not to ascribe any differences to their RMC experience.

Results

Attitudes

We first consider the fundamental beliefs that these students hold about civic life: including satisfaction with democracy, generalized trust, beliefs about politicians and government, and interest in politics.

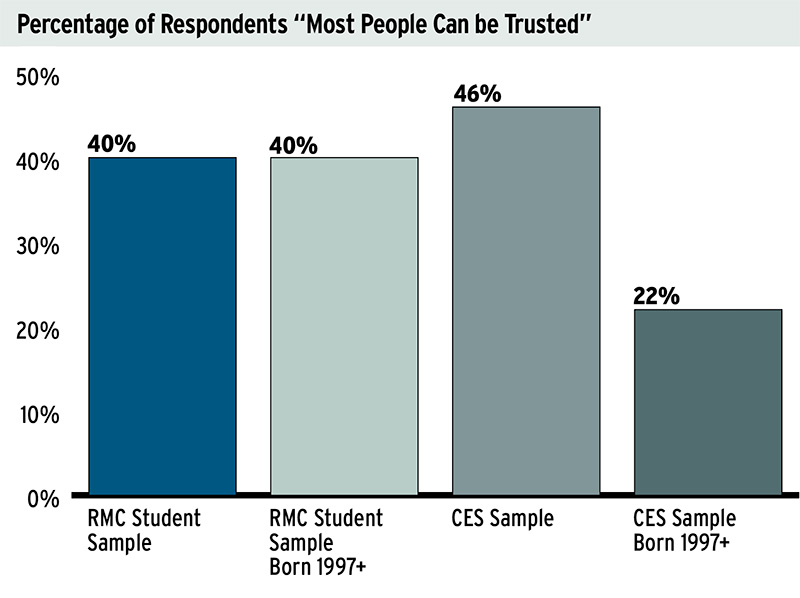

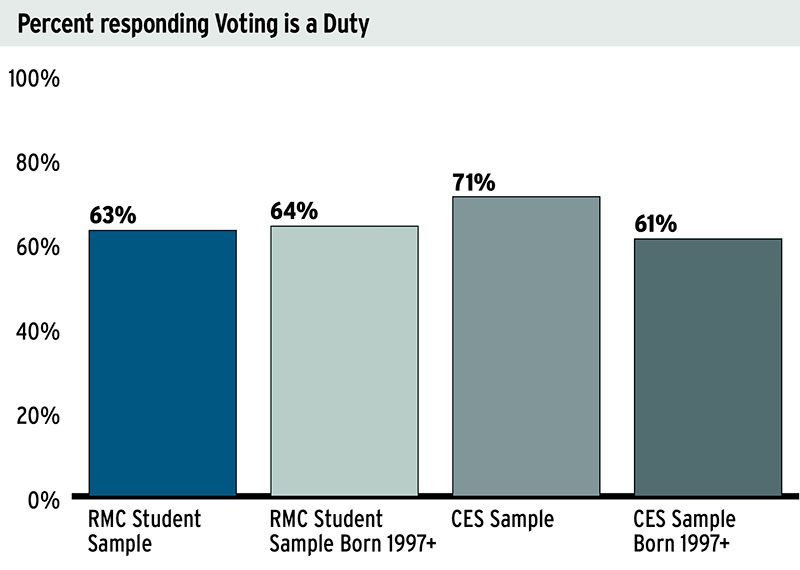

We first note generalized trust to be higher in RMC students than their civilian peer group, but slightly lower than the general population (Figure 1). This is unsurprising given that generalized trust is known to increase with age; research has demonstrated that the youngest cohorts tend to be the least trusting.Footnote 39 It is also unsurprising that these young citizens interested in becoming military officers will be likely to have greater trust in others. Military members are required to have a high degree of trust in their fellow military members, as decisions and actions could have ‘life of death’ consequences. This could be self-selection into the military or skills learned during their short military career thus far.

Figure 1: “Most People can be Trusted” (Generalized Trust)

Question Wording: Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted, or, that you need to be very careful when dealing with people?

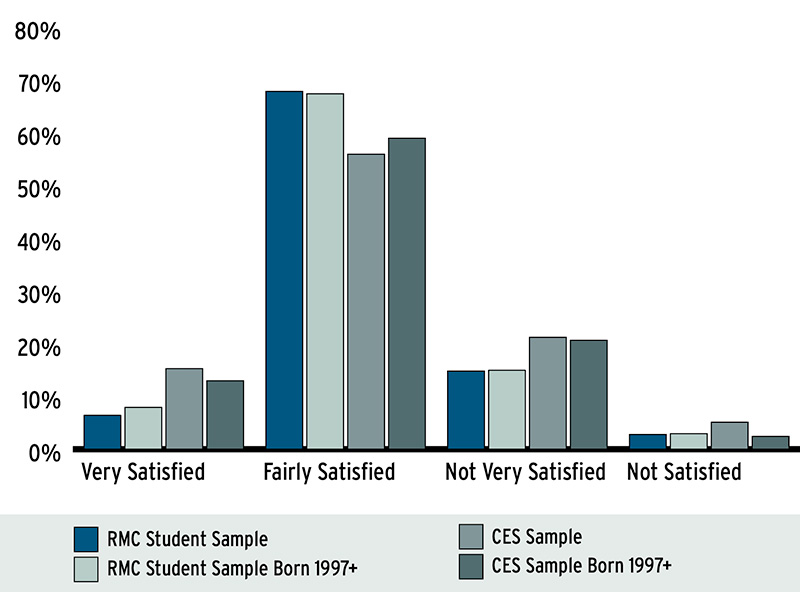

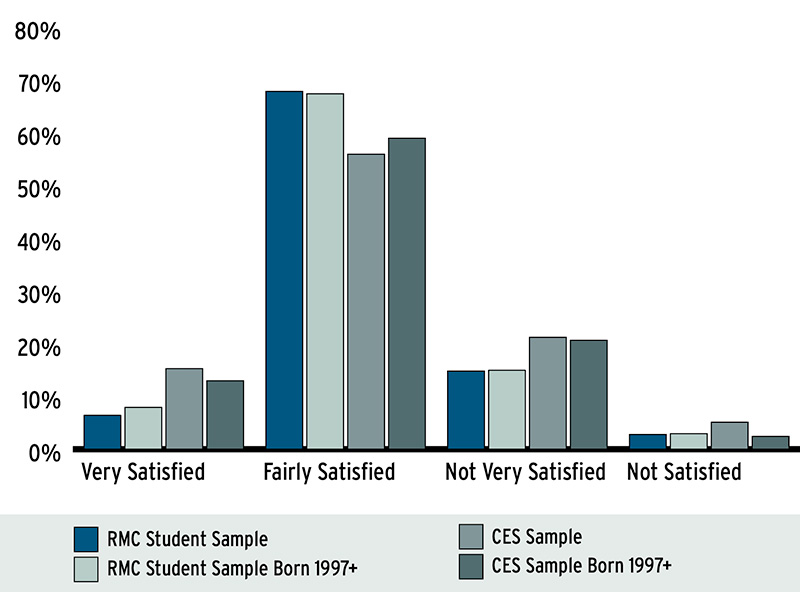

We next consider satisfaction with democracy, asked through the question: “On the whole, are you very satisfied, fairly satisfied, not very satisfied, or not satisfied at all with the way democracy works in Canada?” We note that the RMC student sample tends to have slightly higher responses of being “fairly satisfied” than their peer group and the general population, and consequently are less likely to say they are “not very satisfied” (Figure 2). This points to RMC students being slightly more satisfied with democracy than their peers. Satisfaction with democracy is an important predictor of an individual’s willingness to support how the government is working (and for some scholars, democratic principles more generally).Footnote 40 Thus it makes sense that if an individual is more satisfied with how the democratic system is working, they may be more likely to volunteer to participate in it through military service.

Figure 2: Satisfaction with Democracy

Question Wording: “On the whole, are you very satisfied, fairly satisfied, not very satisfied, or not satisfied at all with the way democracy works in Canada?”

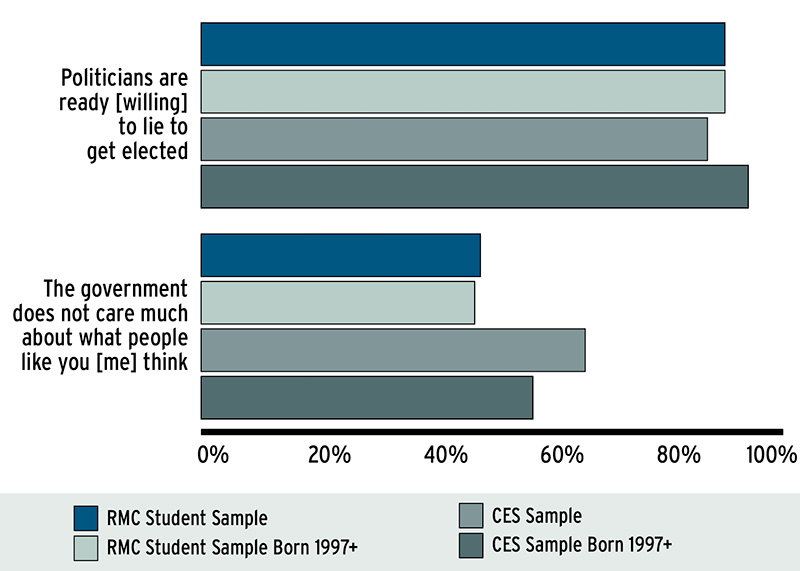

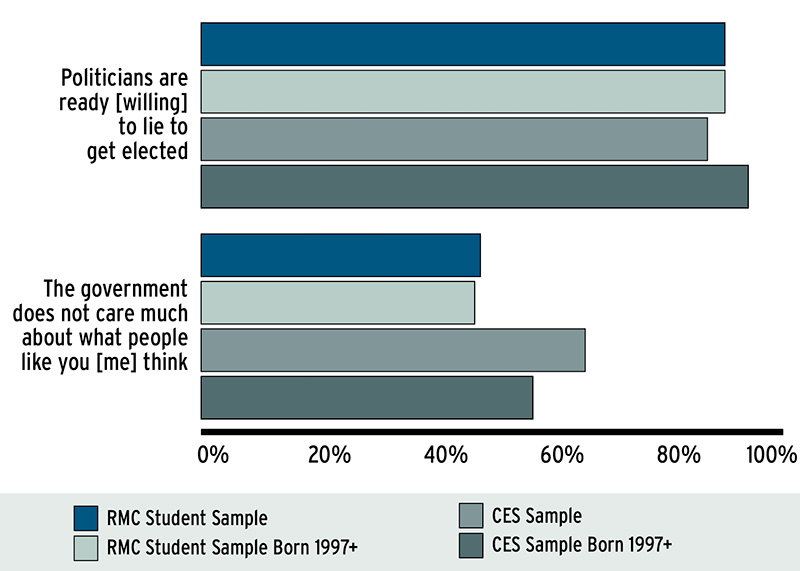

Two questions considered fundamental political opinions. Here we see a similar percentage of respondents who agree or strongly agree with the statement “politicians are ready (willing) to lie to get elected,” with about 90% of RMC students agreeing (Figure 3). This is close to the general population and their peer group and demonstrates a widespread distrust of politicians.

However, we do note lower agreement with the statement “The government does not care much about what people like you think,” at only about 45% of the RMC student sample in affirmative (Figure 3). This provides some indication of higher perception of government caring about their opinions. Again, it is impossible to know for certain whether this is a result of their short military careers, or their opinions and beliefs that led them to enter the military; however, it does demonstrate that RMC students — and future officers — have a bit more confidence in democratic government, unsurprising given their future line of work to uphold it.

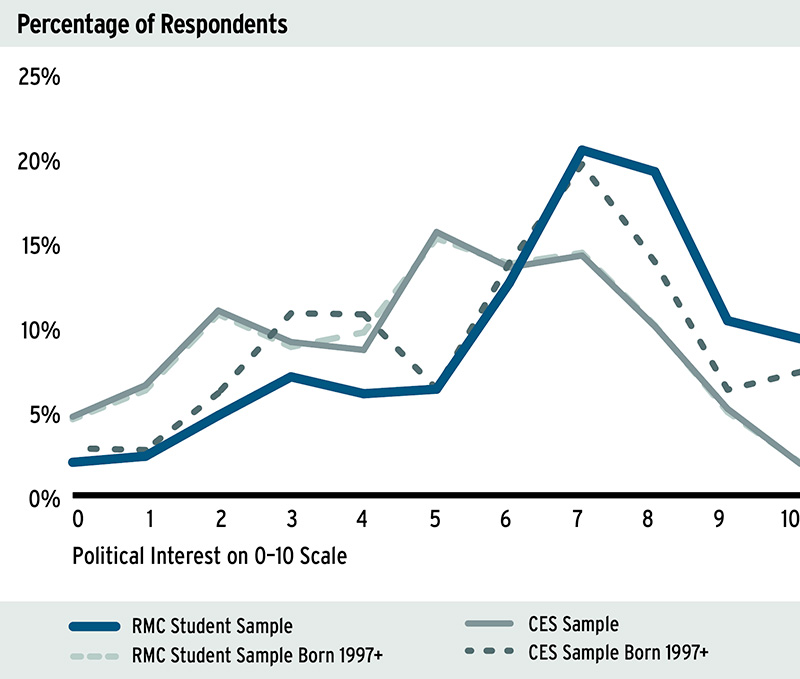

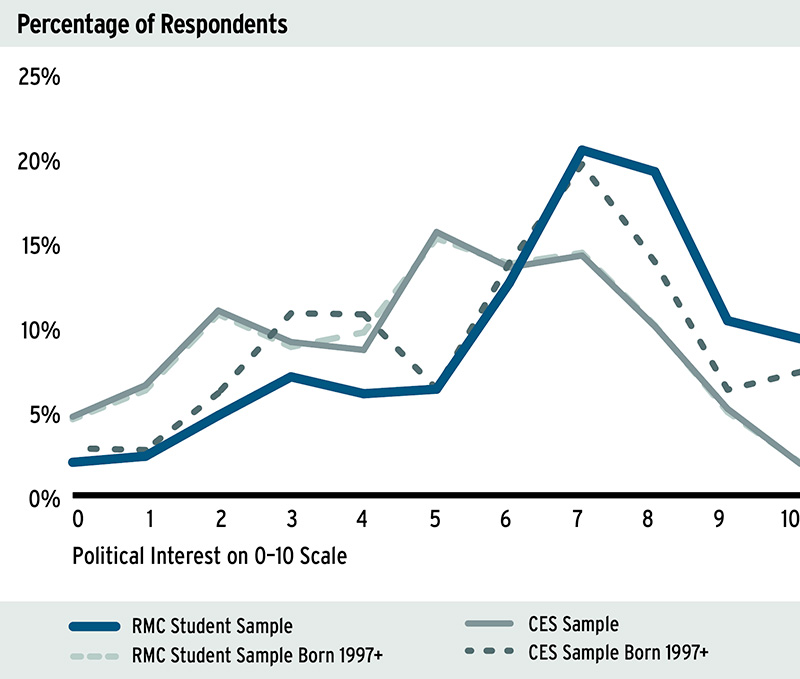

Figure 3: Two Questions from the Battery on Fundamental Political Opinions

Finally, we consider interest in politics (Figure 4). We note the mean political interest score (on a 0—10 scale) is lower for the students surveyed, with the mean for full sample at 4.95; Mean for sample born 1997 and after at 4.92. This is in contrast to the higher means for the general population (6.45) and their peer group (5.8). It is important, however, to note that the CES (from which these data come) tend to have respondents with greater overall interest in politics, as many respondents would simply not be willing to take a long survey about politics unless they had some preliminary interest in the topic. On the contrary, RMC students in the POE/F 205 course from which our sample of students was drawn are taking a required course, and thus did not self-select into the survey (though all had the option to withdraw at any time).

Figure 4: Self-Reported Political Interest

Question Wording: How interested are you in politics GENERALLY? Use a scale from 0 to 10, where zero means no interest at all, and ten means a great deal of interest.

Behaviours

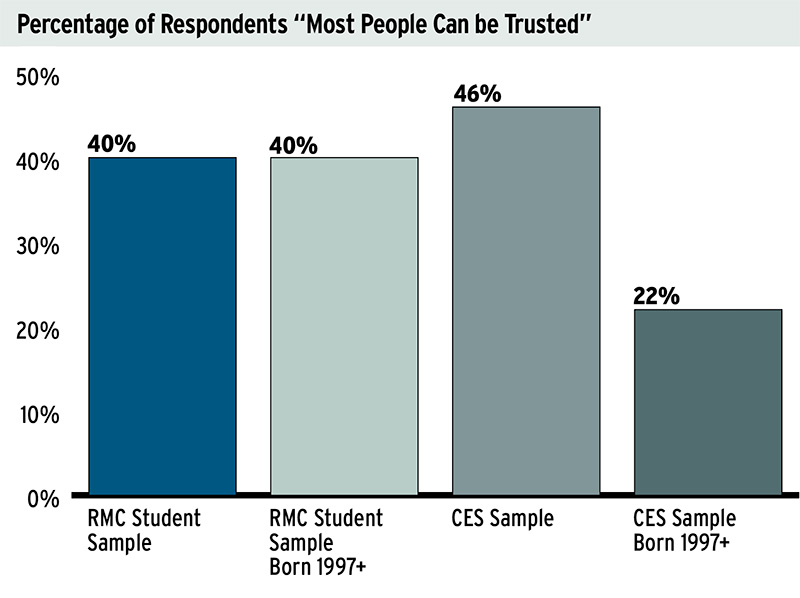

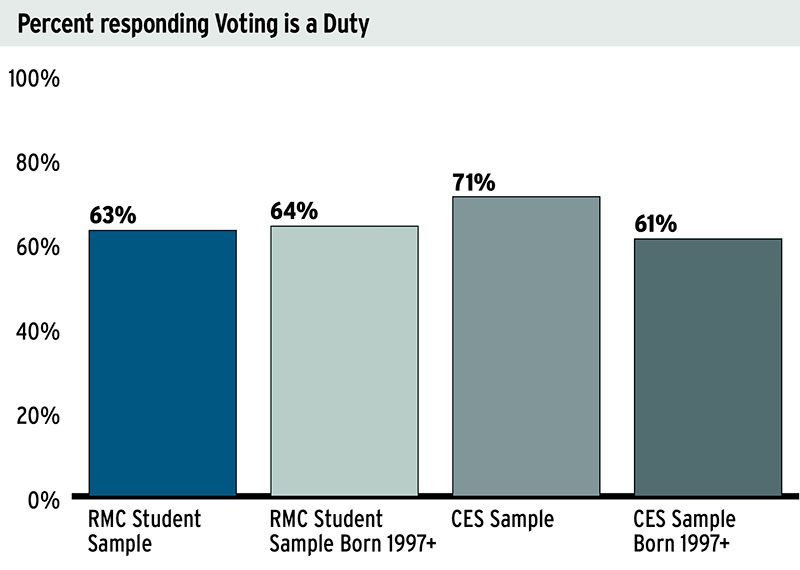

We now turn to political behaviours, that translate the above variables of attitudes and interests into action. Firstly, we consider voting. Since many of the students were unable to vote in the previous election (as they were underage) and we know that turnout is often subject to recall and desirability bias, we use the question of whether the respondent agrees that voting is a duty or a choice (Figure 5). But we know that a sense of duty to vote is a key predictor of turnout.Footnote 41 We note that student respondents tended to be more likely to state that voting was a duty than their peer group, but not more likely than the general population. This corresponds to expectations: young military members know that their lives are directly affected by government decisions, or they may have a keener sense of civic duty (either self-selected for those who choose to enter the military or instilled in them during training).

Figure 5: Respondents who Agree Voting is a Duty (not a choice)

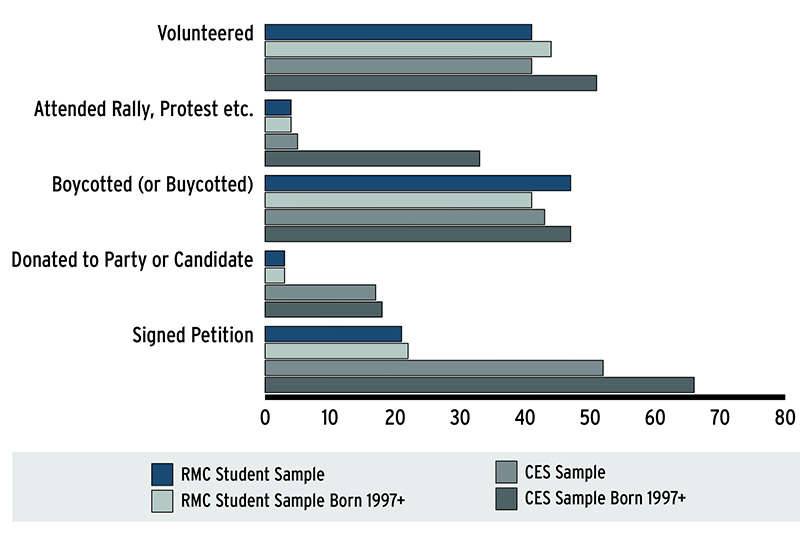

We also compare the RMC students on alternative modes of political participation. Students (and the comparison group) were asked how often they had done one of the following civic activities, from volunteering to signing a petition, in the last 12 months (Figure 6). Here we note some ‘occupational hazards’ on display. We see similar results between the RMC student population and the general population sample for two political activities: volunteering and boycotting (or “boycotting”). It is notable that these two actions are not prohibited by the CAF, whereas there are limitations on other more overt, or traditional, political activities. We see a much lower likelihood of responding they had attended a rally or protest, donated to a party or candidate, or signed a petition. These remain less likely than even their peer group. Thus, while their military service may in some cases bolster civic mindedness (for example, a duty to vote), for other forms of participation not sanctioned by (or discouraged by) the CAF, young military members are stifled in their ability to exercise their political attitudes with alternative forms of action.

Figure 6: Means of Political Participation

“Have you done any of the following things in the last 12 months?”

See question wording differences in Appendix.

Conclusion

This article considered the differences in fundamental political attitudes and behaviours between (primarily) young future military officers at RMC, and the general Canadian population. We undertook a survey of RMC students between 2019 and 2022 as part of the POE/F 205: Canadian Politics and Society/Politique et société canadiennes course, comparing their responses to those given in the 2019 CES.

We find that the RMC students surveyed do show a small attitudinal gap when compared with their peer group and the general population. We note that RMC students’ generalized trust is higher (closer to the general population) than their peer group of fellow young Canadians born after 1997. Additionally, we see some greater general satisfaction with the way democracy works than their peer group, which we suspect may be part of the reason they chose to enter the military in the first place, rather than an RMC socialization effect, though we cannot be certain. At the same time, we note that the RMC students have lower general political interest, although we know that the CES sample tends to consist of citizens more politically interested to respond to the survey.

We note that political behaviours are similar between the RMC students and the general population for activities that are generally not openly discouraged within the CAF, including a sense of duty to vote, volunteering and buying or boycotting items. However, they do have lower levels of partisan political activities (which are not permitted for CAF members), and other more discouraged forms of participation like attendance at rallies or signing petitions. This demonstrates some “occupational hazard” surrounding the development of political activism among these future officers. Future research may consider how the stifling of political activities in the young impressionable years may impact how they engage in civic life in the long term, post-release from the CAF.

There remain limitations to this research, notably the question of causality: are these differences in attitudes and behaviours a result of self-selection into the CAF? Or do they emerge during, and as a result of, their training at RMC? Further longitudinal study considering how attitudes change from before and after a student’s time at RMC could address this question.

In sum, this research contributes to our understanding of how future military officers’ political opinions and behaviours differ from their peer group and the general population of Canadians. It shows that these young future military officers can, in fact, have different approaches to politics from the population they serve. These findings may be of use for those training future officers in the civic values desired by the CAF, in particular through the RMC core curriculum.

Appendix: Question wording

| Variable | Example | Survey Question |

|---|---|---|

|

Generalized Trust |

|

Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted, or, that you need to be very careful when dealing with people? Most people can be trusted. (0) You need to be very careful when dealing with others. (1) Don’t know (99) |

|

Satisfaction with Democracy |

|

On the whole, are you very satisfied, fairly satisfied, not very satisfied, or not satisfied at all with the way democracy works in Canada? Very satisfied (0) Fairly satisfied (1) Not very satisfied (2) Not satisfied at all (3) Don’t know (99) |

|

Fundamental Political Beliefs |

|

Do you strongly agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, or strongly disagree with the following statements? The government does not care much about what people like you think. (CES Question – pes19_govtcare “The government does not care much about what people like me think.”) Politicians are ready to lie to get elected. (CES Question pes19_pollie “Politicians are willing to lie to get elected.”) |

|

Interest in Politics |

|

How interested are you in politics GENERALLY? Use a scale from 0 to 10, where zero means no interest at all, and ten means a great deal of interest. 1 – no interest at all (0) 2 (1) 3 (2) 4 (3) 5 (4) 6 (5) 7 (6) 8 (7) 9 (8) 10 – a great deal of interest (9) |

|

Voting a Duty or Choice |

|

People have different views about voting. For some, voting is a DUTY. They feel that they should vote in every election. For others, voting is a CHOICE. They only vote when they feel strongly about that election. For you personally, is voting FIRST AND FOREMOST a Duty or a Choice? Duty (0) Choice (1) Don’t know (99) |

|

Political Behaviours/Activities |

|

Have you done any of the following things in the last 12 months? Have you signed a petition? Have you donated money to a political party or candidate? Have you bought products for political, ethical, or environment reasons? (CES Question Boycotted or bought products for ethical, environmental, or political reasons) Have you taken part in a march, rally, or protest? (CES Question Attended a rally or participated in a protest or demonstration) Have you volunteered for a group or organization like a school, religious organization, sports, or community associations? |